The State of Reinforcement Learning for LLM Reasoning

Understanding GRPO and New Insights from Reasoning Model Papers

A lot has happened this month, especially with the releases of new flagship models like GPT-4.5 and Llama 4. But you might have noticed that reactions to these releases were relatively muted. Why? One reason could be that GPT-4.5 and Llama 4 remain conventional models, which means they were trained without explicit reinforcement learning for reasoning.

Meanwhile, competitors such as xAI and Anthropic have added more reasoning capabilities and features into their models. For instance, both the xAI Grok and Anthropic Claude interfaces now include a “thinking” (or “extended thinking”) button for certain models that explicitly toggles reasoning capabilities.

In any case, the muted response to GPT-4.5 and Llama 4 (non-reasoning) models suggests we are approaching the limits of what scaling model size and data alone can achieve.

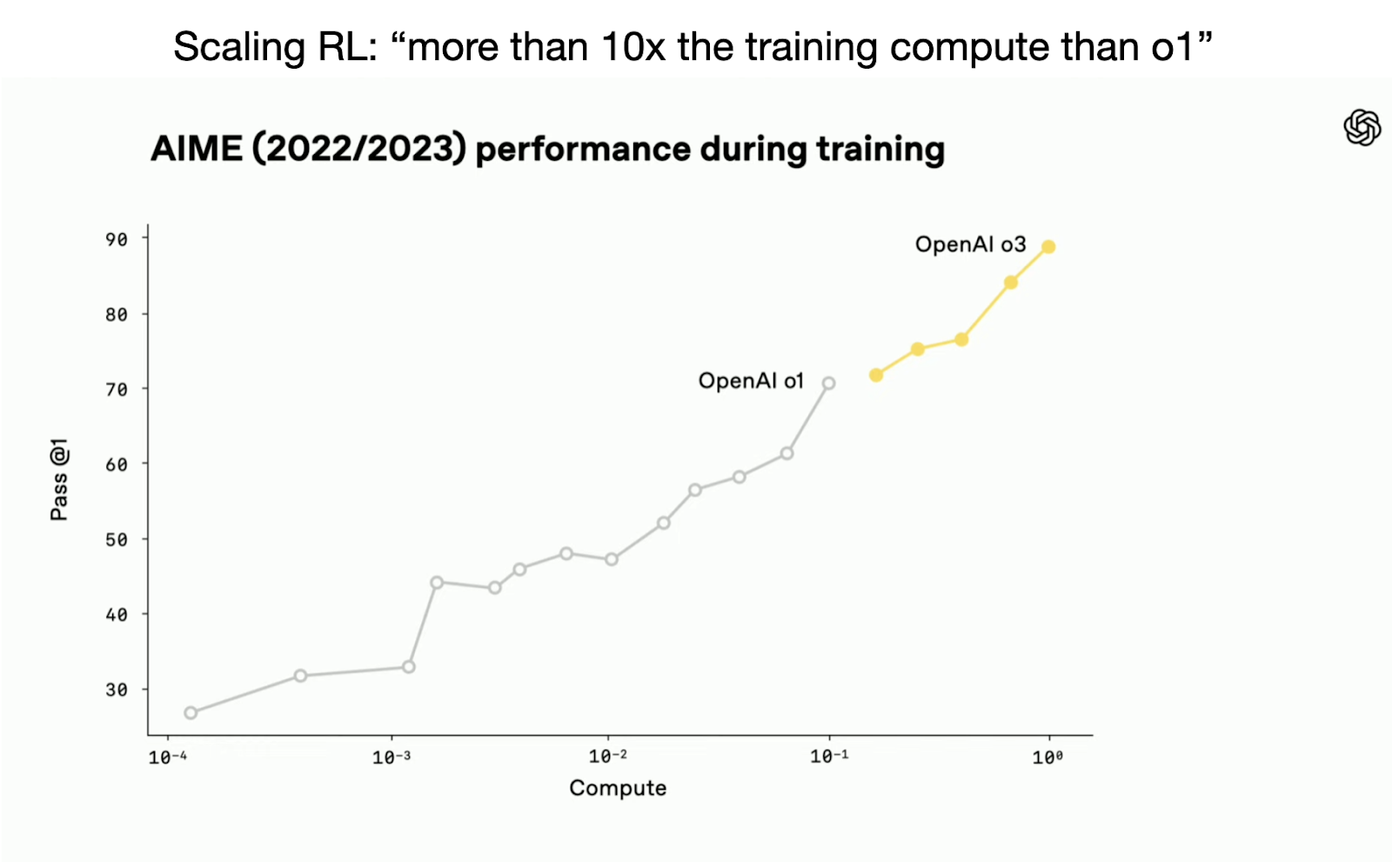

However, OpenAI’s recent release of the o3 reasoning model demonstrates there is still considerable room for improvement when investing compute strategically, specifically via reinforcement learning methods tailored for reasoning tasks. (According to OpenAI staff during the recent livestream, o3 used 10× more training compute compared to o1.)

While reasoning alone isn’t a silver bullet, it reliably improves model accuracy and problem-solving capabilities on challenging tasks (so far). And I expect reasoning-focused post-training to become standard practice in future LLM pipelines.

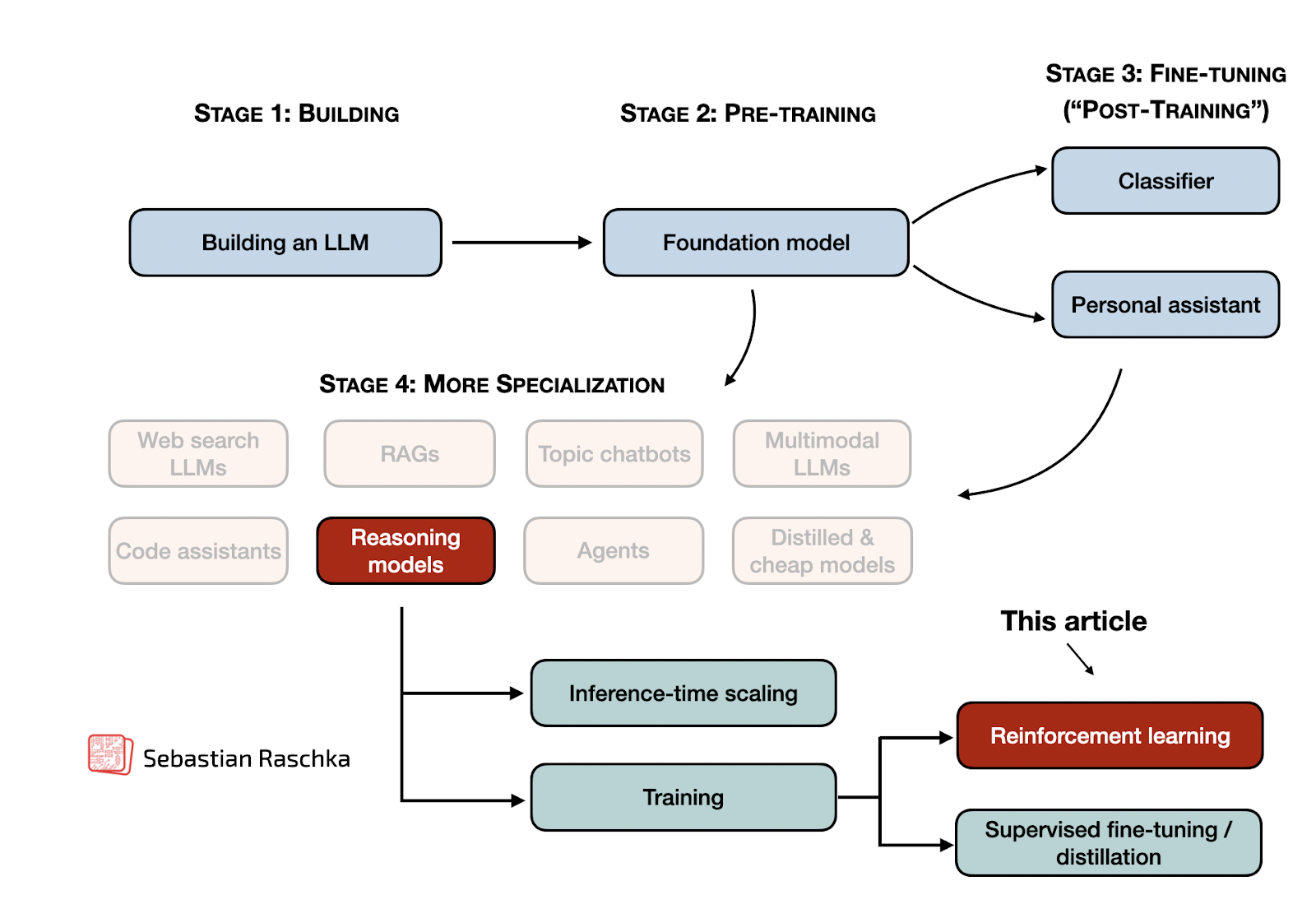

So, in this article, let’s explore the latest developments in reasoning via reinforcement learning.

Because it is a relatively long article, I am providing a Table of Contents overview below. To navigate the table of contents, please use the slider on the left-hand side in the web view.

- Understanding reasoning models

- RLHF basics: where it all started

- A brief introduction to PPO: RL’s workhorse algorithm

- RL algorithms: from PPO to GRPO

- RL reward modeling: from RLHF to RLVR

- How the DeepSeek-R1 reasoning models were trained

- Lessons from recent RL papers on training reasoning models

- Noteworthy research papers on training reasoning models

Tip: If you are already familiar with reasoning basics, RL, PPO, and GRPO, please feel free to directly jump ahead to the “Lessons from recent RL papers on training reasoning models” section, which contains summaries of interesting insights from recent reasoning research papers.

Understanding reasoning models

The big elephant in the room is, of course, the definition of reasoning. In short, reasoning is about inference and training techniques that make LLMs better at handling complex tasks.

To provide a bit more detail on how this is achieved (so far), I’d like to define reasoning as follows:

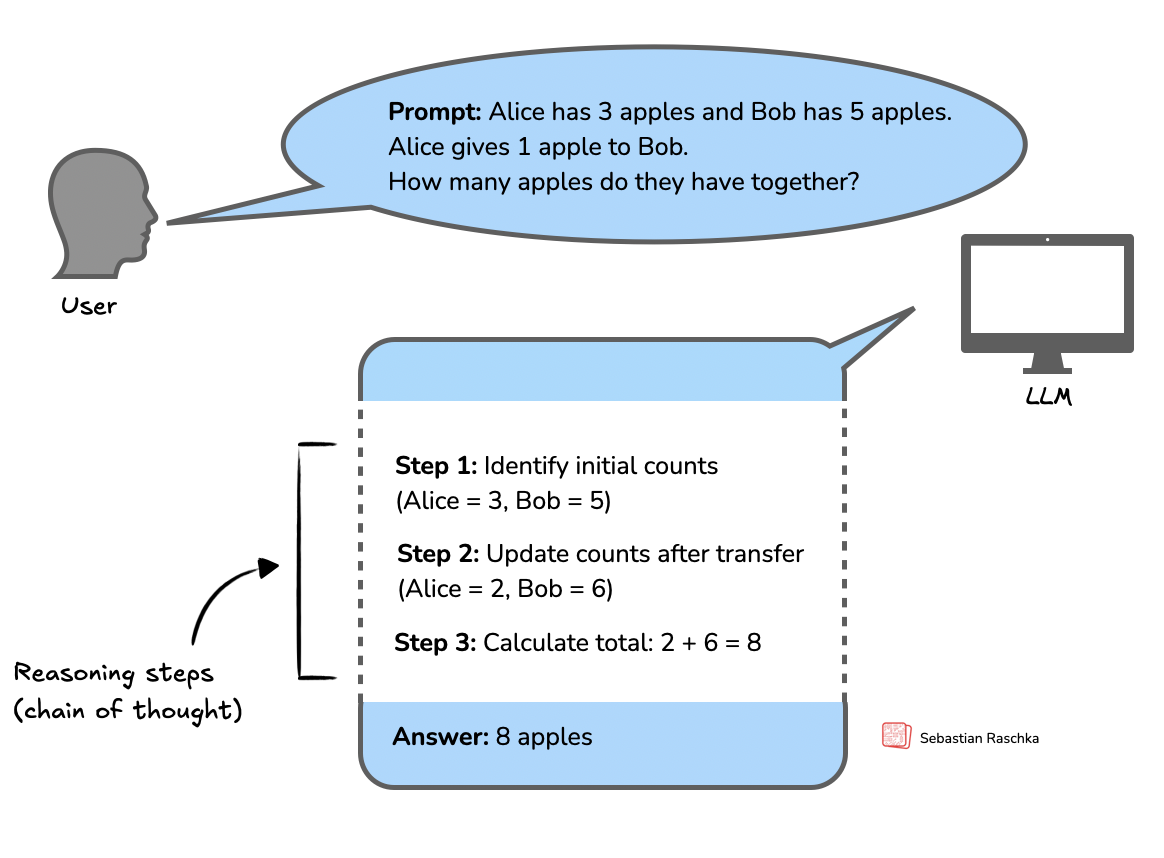

Reasoning, in the context of LLMs, refers to the model’s ability to produce intermediate steps before providing a final answer. This is a process that is often described as chain-of-thought (CoT) reasoning. In CoT reasoning, the LLM explicitly generates a structured sequence of statements or computations that illustrate how it arrives at its conclusion.

And below is a figure along with the definition.

If you are new to reasoning models and would like a more comprehensive introduction, I recommend my previous articles:

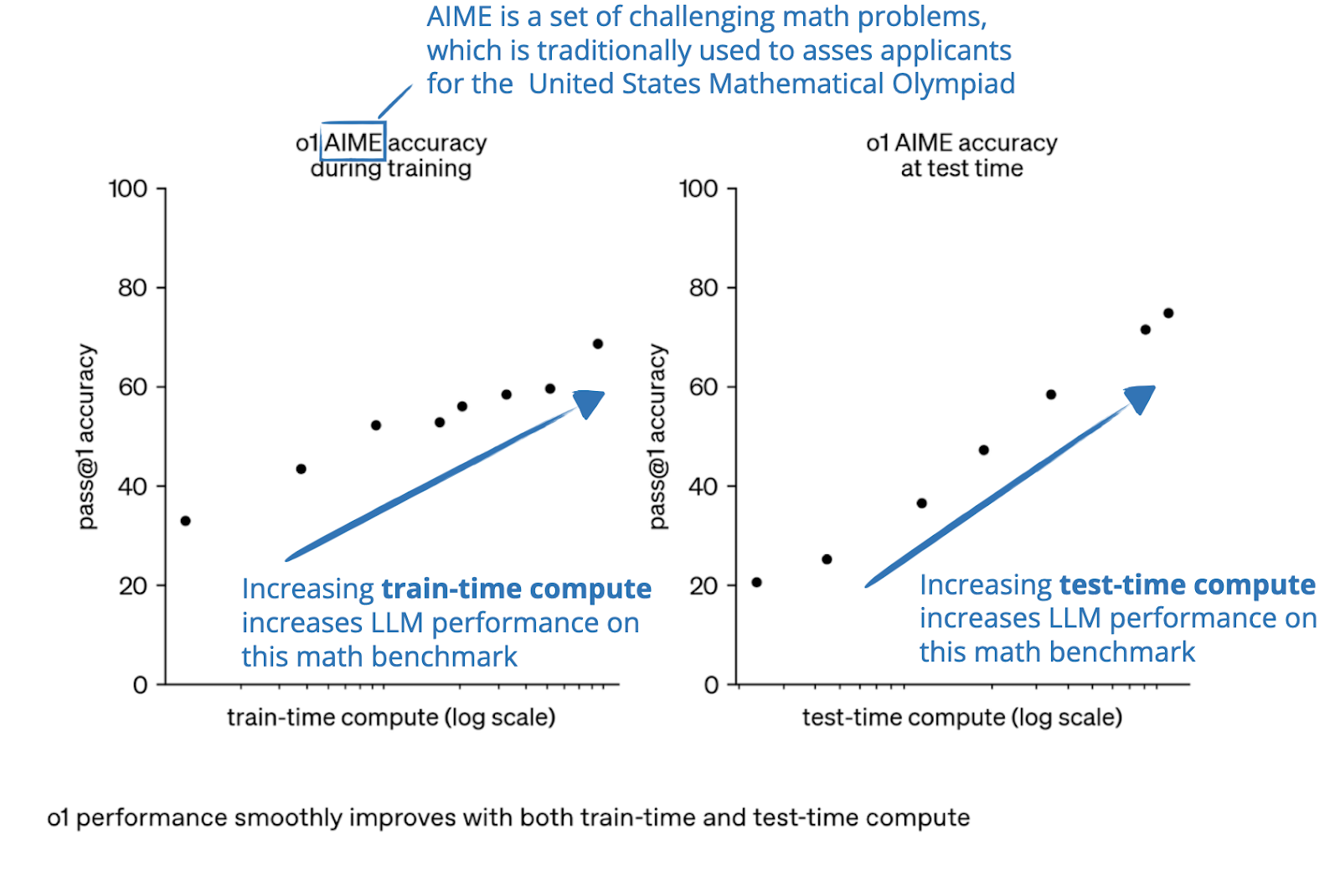

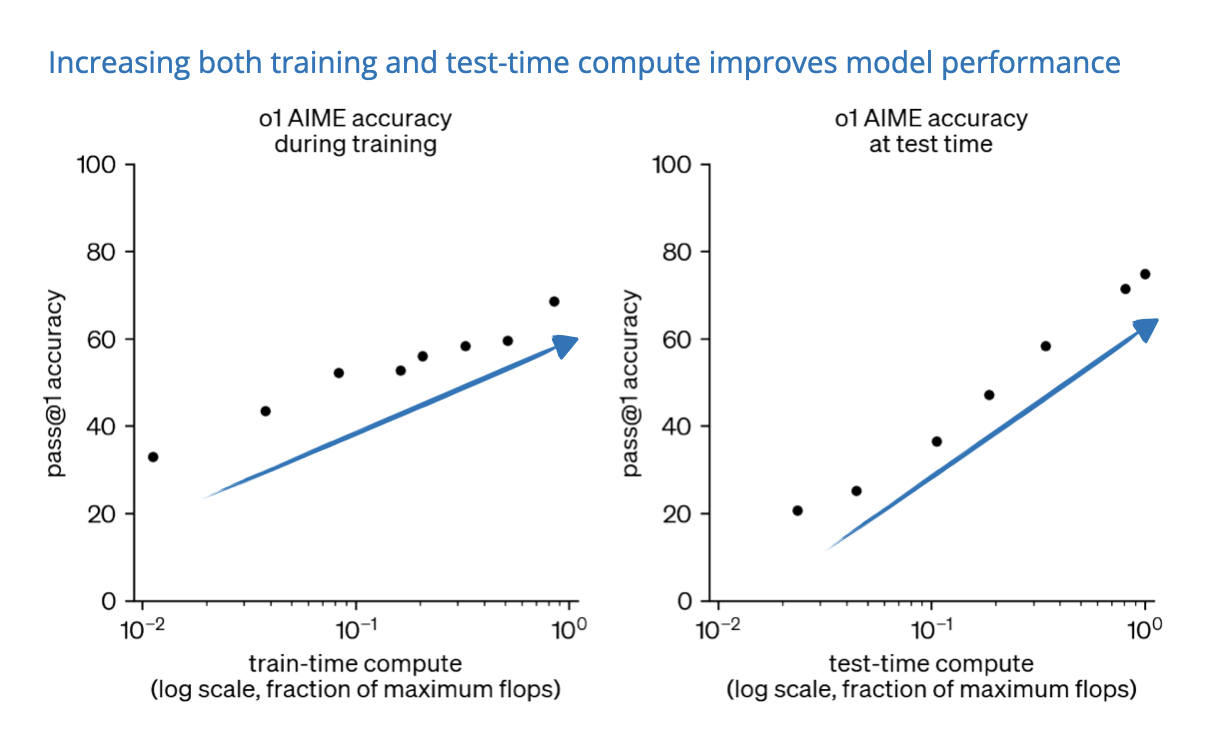

Now, as hinted at the beginning of this section, the reasoning abilities of LLMs can be improved in two ways, as nicely illustrated in a figure from an OpenAI blog post:

In my previous article The State of LLM Reasoning Model Inference, I solely focused on the test-time compute methods. In this article, I finally want to take a closer look at the training methods.

RLHF basics: where it all started

The reinforcement learning (RL) training methods used to build and improve reasoning models are more or less related to the reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF) methodology that is used to develop and align conventional LLMs. So, I want to start with a small recap of how RLHF works before discussing reasoning-specific modification based on RL-based training.

Conventional LLMs typically undergo a 3-step training procedure:

- Pre-training

- Supervised fine-tuning

- Alignment (typically via RLHF)

The “original” LLM alignment method is RLHF, which is part of the standard repertoire when developing LLMs following the InstructGPT paper, which described the recipe that was used to develop the first ChatGPT model.

The original goal of RLHF is to align LLMs with human preferences. For instance, suppose you use an LLM multiple times where the LLM generates multiple answers for a given prompt. RLHF guides the LLM towards generating more of the style of answer that you prefer. (Often, RLHF is also used to safety-tune LLMs: to avoid sharing sensitive information, using swear words, and so on.)

If you are new to RLHF, here is an excerpt from a talk I gave a few years ago that explains RLHF in less than 5 minutes:

Alternatively, the paragraphs below describe RLHF in text form.

The RLHF pipeline takes a pre-trained model and fine-tunes it in a supervised fashion. This fine-tuning is not the RL part yet but is mainly a prerequisite.

Then, RLHF further aligns the LLM using an algorithm called proximal policy optimization (PPO). (Note that there are other algorithms that can be used instead of PPO; I was specifically saying PPO because that’s what was originally used in RLHF and is still the most popular one today.)

For simplicity, we will look at the RLHF pipeline in three separate steps:

- RLHF Step 1 (prerequisite): Supervised fine-tuning (SFT) of the pre-trained model

- RLHF Step 2: Creating a reward model

- RLHF Step 3: Fine-tuning via proximal policy optimization (PPO)

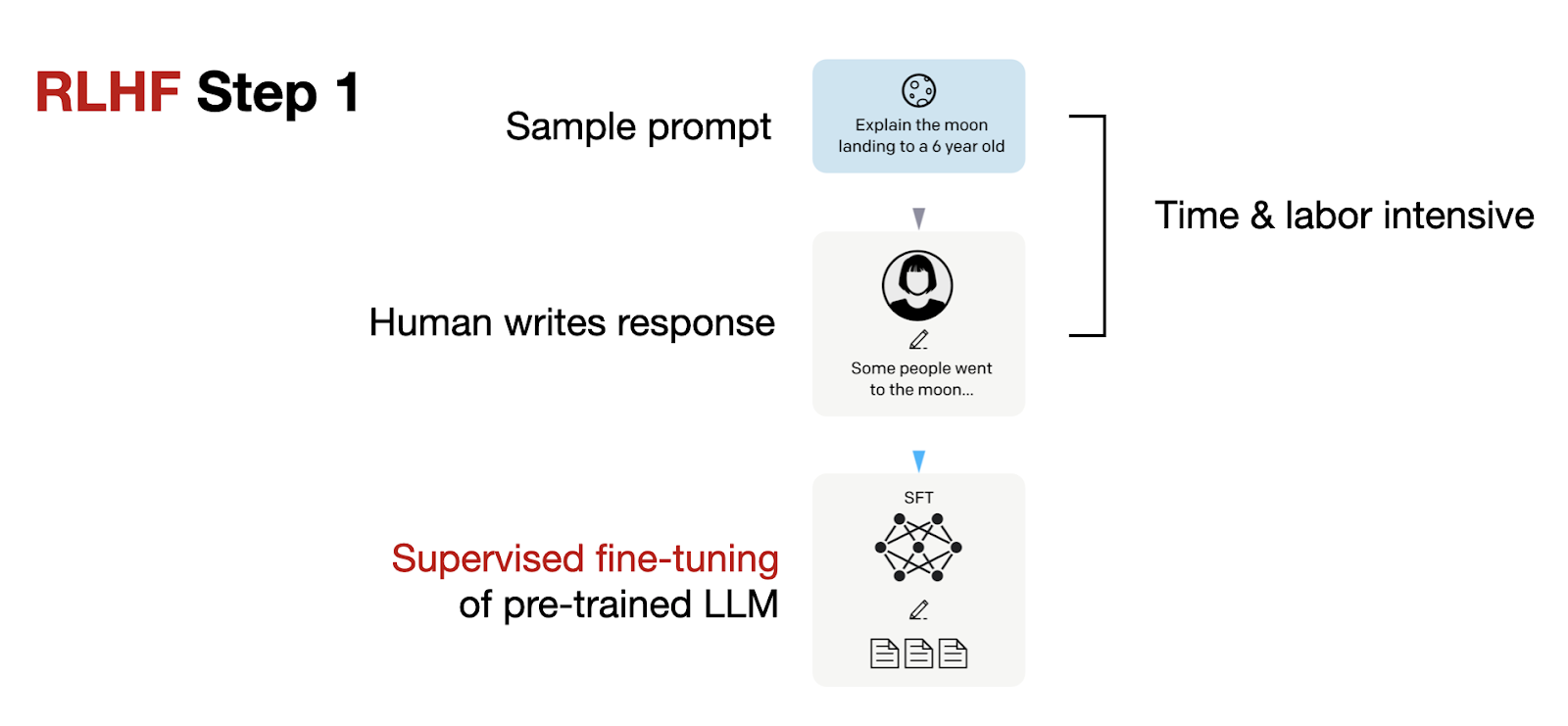

RLHF Step 1, shown below, is a supervised fine-tuning step to create the base model for further RLHF fine-tuning.

In RLHF step 1, we create or sample prompts (from a database, for example) and ask humans to write good-quality responses. We then use this dataset to fine-tune the pre-trained base model in a supervised fashion. As mentioned before, this is not technically part of RL training but merely a prerequisite.

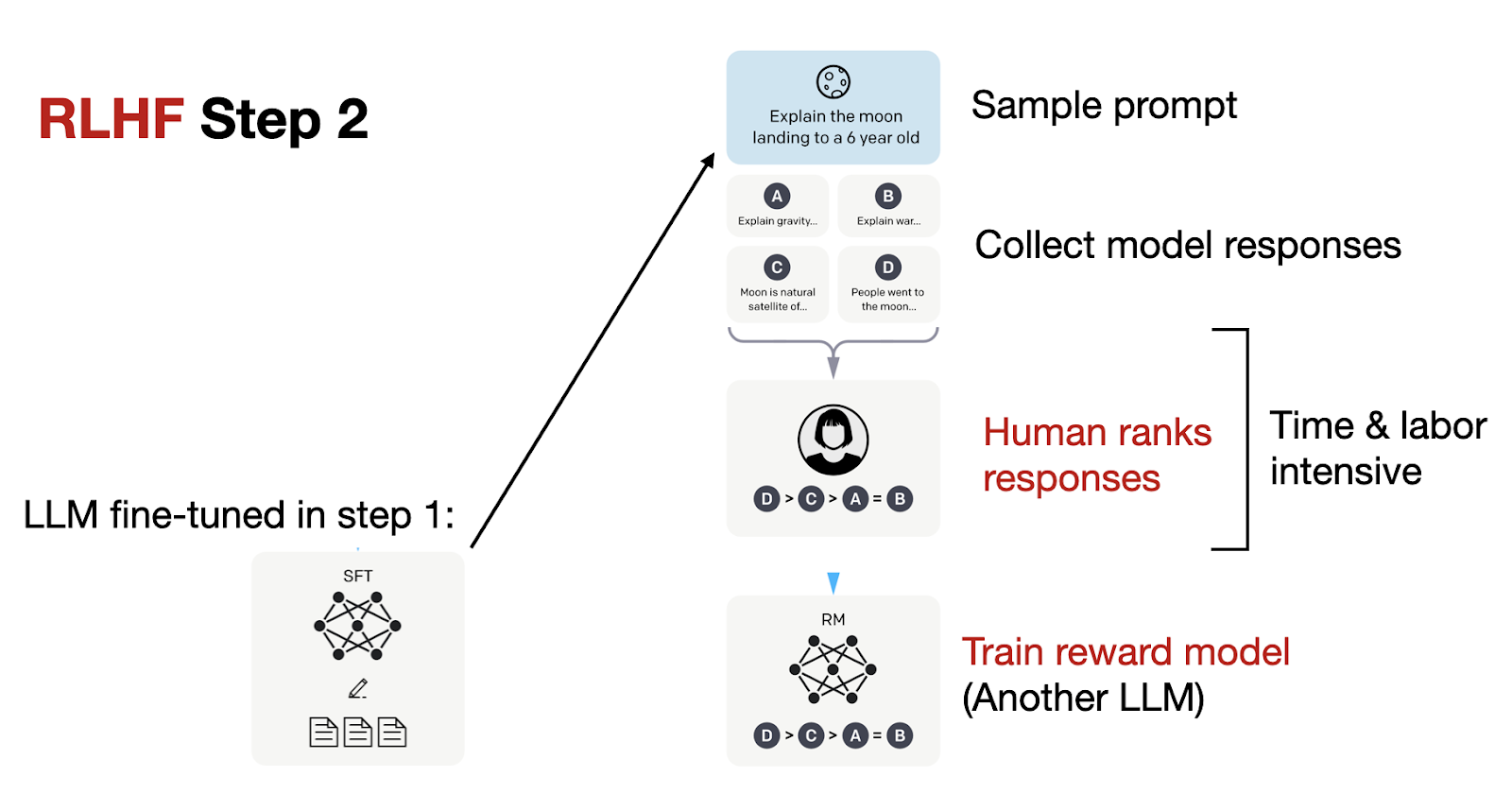

In RLHF Step 2, we then use this model from supervised fine-tuning (SFT) to create a reward model, as shown below.

As depicted in the figure above, for each prompt, we generate four responses from the fine-tuned LLM created in the prior step. Human annotators then rank these responses based on their preferences. Although this ranking process is time-consuming, it might be somewhat less labor-intensive than creating the dataset for supervised fine-tuning. This is because ranking responses is likely simpler than writing them.

Upon compiling a dataset with these rankings, we can design a reward model that outputs a reward score for the optimization subsequent stage in RLHF Step 3. The idea here is that the reward model replaces and automates the labor-intensive human ranking to make the training feasible on large datasets.

This reward model (RM) generally originates from the LLM created in the prior supervised fine-tuning (SFT) step. To turn the model from RLHF Step 1 into a reward model, its output layer (the next-token classification layer) is substituted with a regression layer, which features a single output node.

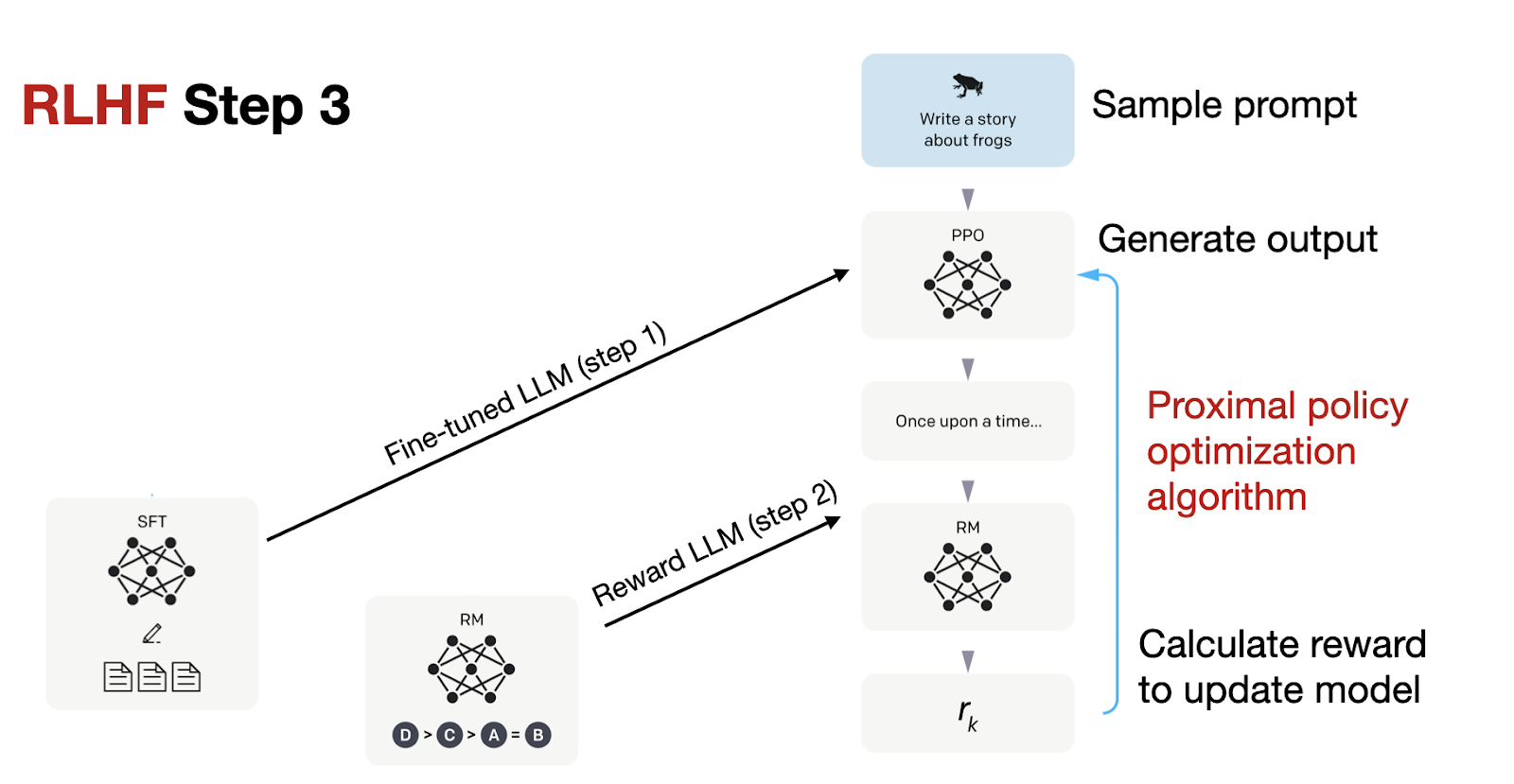

The third step in the RLHF pipeline is to use the reward model (RM) to fine-tune the previous model from supervised fine-tuning (SFT), which is illustrated in the figure below.

In RLHF Step 3, the final stage, we are now updating the SFT model using proximal policy optimization (PPO) based on the reward scores from the reward model we created in RLHF Step 2.

Ahead of AI is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Subscribe

A brief introduction to PPO: RL’s workhorse algorithm

As mentioned earlier, the original RLHF method uses a reinforcement learning algorithm called proximal policy optimization (PPO).

PPO was developed to improve the stability and efficiency of training a policy. (In reinforcement learning, “policy” just means the model we want to train; in this case, policy = LLM.)

One of the key ideas behind PPO is that it limits how much the policy is allowed to change during each update step. This is done using a clipped loss function, which helps prevent the model from making overly large updates that could destabilize training.

On top of that, PPO also includes a KL divergence penalty in the loss. This term compares the current policy (the model being trained) to the original SFT model. This encourages the updates to stay reasonably close. The idea is to preference-tune the model, not to completely re-train, after all.

This is where the “proximal” in proximal policy optimization comes from: the algorithm tries to keep the updates close to the existing model while still allowing for improvement. And to encourage a bit of exploration, PPO also adds an entropy bonus, which this encourages the model to vary the outputs during training.

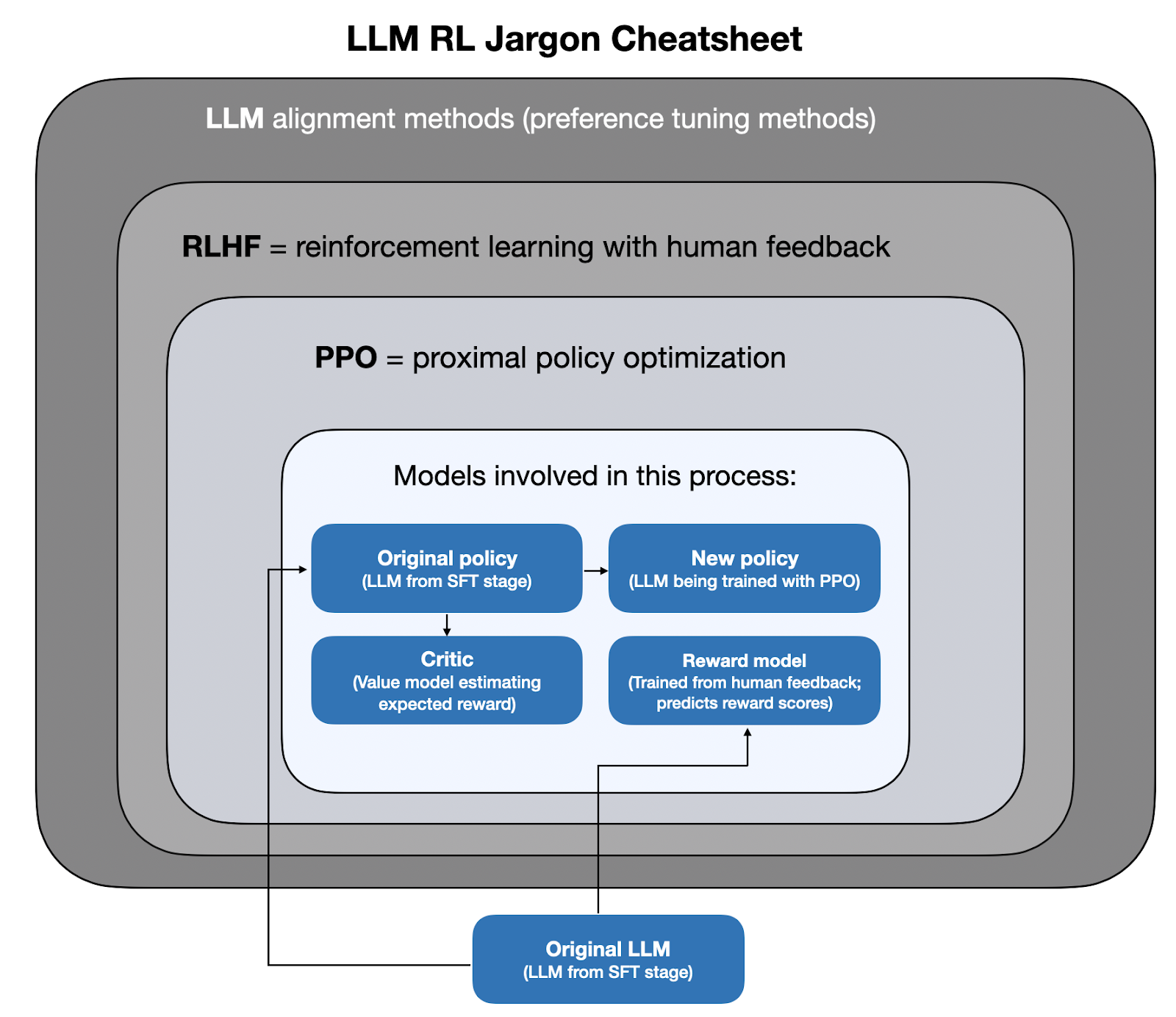

In the following paragraphs, I want to introduce some more terminology to illustrate PPO on a relatively high level. Still, there’s a lot of jargon involved, so I tried to summarize the key terminology in the figure below before we continue.

Below, I aim to illustrate the key steps in PPO via pseudo-code.

In addition, to make it more intuitive, I will also use an analogy: Imagine you are a chef running a small food delivery service. And you are constantly trying out new recipe variations to improve customer satisfaction. Your overall goal is to tweak your recipe (policy) based on customer feedback (reward).

1. Compute the ratio of the next-token probabilities from the new vs the old policy:

ratio = new_policy_prob / old_policy_prob

In short, this checks how different our new recipe is from the old one.

Side note: Regarding “new_policy_prob”, we are not using the final updated policy yet. We are using the current version of the policy (i.e., the model we are in the middle of training). However, it’s a convention to call it “new”. So, even though you’re still experimenting, we call your current draft the “new policy” as per convention.

2. Multiply that ratio by how good the action was (called the advantage):

raw_score = ratio * advantage

Here, for simplicity, we may assume the advantage is computed based on the reward signal:

advantage = actual_reward - expected_reward

In the chef analogy, we can think of the advantage as how well the new dish performed:

advantage = customer_rating - expected_rating

For example, if a customer rates the new dish with a 9/10, and the customers normally give us a 7/10, that’s a +2 advantage.

Note that this is a simplification. In reality, this involves generalized advantage estimation (GAE), which I am omitting here so as not to bloat the article further. However, one important detail to mention is that the expected reward is computed by a so-called “critic” (sometimes also called “value model”), and a reward model computes the actual reward. I.e., the advantage computation involves 2 other models, typically the same size as the original model we are fine-tuning.

In the analogy, we can think of this critic or value model as a friend we ask to try our new dish before serving it to the customers. We also ask our friend to estimate how a customer would rank it (that’s the expected reward). The reward model is the actual customer then who gives the feedback (i.e., the actual reward).

3. Compute a clipped score:

If the new policy changes too much (e.g., ratio > 1.2 or < 0.8), we clip the ratio, as follows:

clipped_ratio = clamp(ratio, 0.8, 1.2)

clipped_score = clipped_ratio * advantage

In the analogy, imagine that the new recipe got an exceptionally great (or bad) review. We might be tempted to overhaul the entire menu now. But that’s risky. So, instead, we clip how much our recipe can change for now. (For instance, maybe we made the dish much spicier, and that one customer happened to love spicy food, but that doesn’t mean everyone else will.)

4. Then we use the smaller of the raw score and clipped score:

if advantage >= 0:

final_score = min(raw_score, clipped_score)

else:

final_score = max(raw_score, clipped_score)

Again, this is related to being a bit cautious. For instance, if the advantage is positive (the new behavior is better), we cap the reward. That’s because we don’t want to over-trust a good result that might be a coincidence or luck.

If the advantage is negative (the new behavior is worse), we limit the penalty. The idea here is similar. Namely, we don’t want to overreact to one bad result unless we are really sure.

In short, we use the smaller of the two scores if the advantage is positive (to avoid over-rewarding), and the larger when the advantage is negative (to avoid over-penalizing).

In the analogy, this ensures that if a recipe is doing better than expected, we don’t over-reward it unless we are confident. And if it’s underperforming, we don’t over-penalize it unless it’s consistently bad.

5. Calculating the loss:

This final score is what we maximize during training (using gradient descent after flipping the sign of the score to minimize). In addition, we also add a KL penalty term, where β is a hyperparameter for the penalty strength:

loss = -final_score + β * KL(new_policy || reference_policy)

In the analogy, we add the penalty to ensure new recipes are not too different from our original style. This prevents you from “reinventing the kitchen” every week. For example, we don’t want to turn an Italian restaurant into a BBQ place all of a sudden.

This was a lot of information, so I summarized it with a concrete, numeric example in an LLM context via the figure below. But please feel free to skip it if it’s too complicated; you should be able to follow the rest of the article just fine.

I admit that I may have gone overboard with the PPO walkthrough. But once I had written it, it was hard to delete it. I hope some of you will find it useful!

That being said, the main takeaways that will be relevant in the next section are that there are multiple models involved in PPO:

1. The policy, which is the LLM that has been trained with SFT and that we want to further align).

2. The reward model, which is a model that has been trained to predict the reward (see RLHF step 2).

3. The critic, which is a trainable model that estimates the reward.

4. A reference model (original policy) that we use to make sure that the policy doesn’t deviate too much.

By the way, you might wonder why we need both a reward model and a critic model. The reward model is usually trained before training the policy with PPO. It’s to automate the preference labeling by human judges, and it gives the score for the complete responses generated by the policy LLM.

The critic, in contrast, judges partial responses. We use it to create the final response. While the reward model typically remains frozen, the critic model is updated during training to estimate the reward created by the reward model better.

More details about PPO are out of the scope of this article, but interested readers can find the mathematical details in these four papers that predate the InstructGPT paper:

(1) Asynchronous Methods for Deep Reinforcement Learning (2016) by Mnih, Badia, Mirza, Graves, Lillicrap, Harley, Silver, and Kavukcuoglu introduces policy gradient methods as an alternative to Q-learning in deep learning-based RL.

(2) Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithms (2017) by Schulman, Wolski, Dhariwal, Radford, and Klimov presents a modified proximal policy-based reinforcement learning procedure that is more data-efficient and scalable than the vanilla policy optimization algorithm above.

(3) Fine-Tuning Language Models from Human Preferences (2020) by Ziegler, Stiennon, Wu, Brown, Radford, Amodei, Christiano, Irving illustrates the concept of PPO and reward learning to pretrained language models including KL regularization to prevent the policy from diverging too far from natural language.

(4) Learning to Summarize from Human Feedback (2022) by Stiennon, Ouyang, Wu, Ziegler, Lowe, Voss, Radford, Amodei, Christiano introduces the popular RLHF three-step procedure that was later also used in the InstructGPT paper.

RL algorithms: from PPO to GRPO

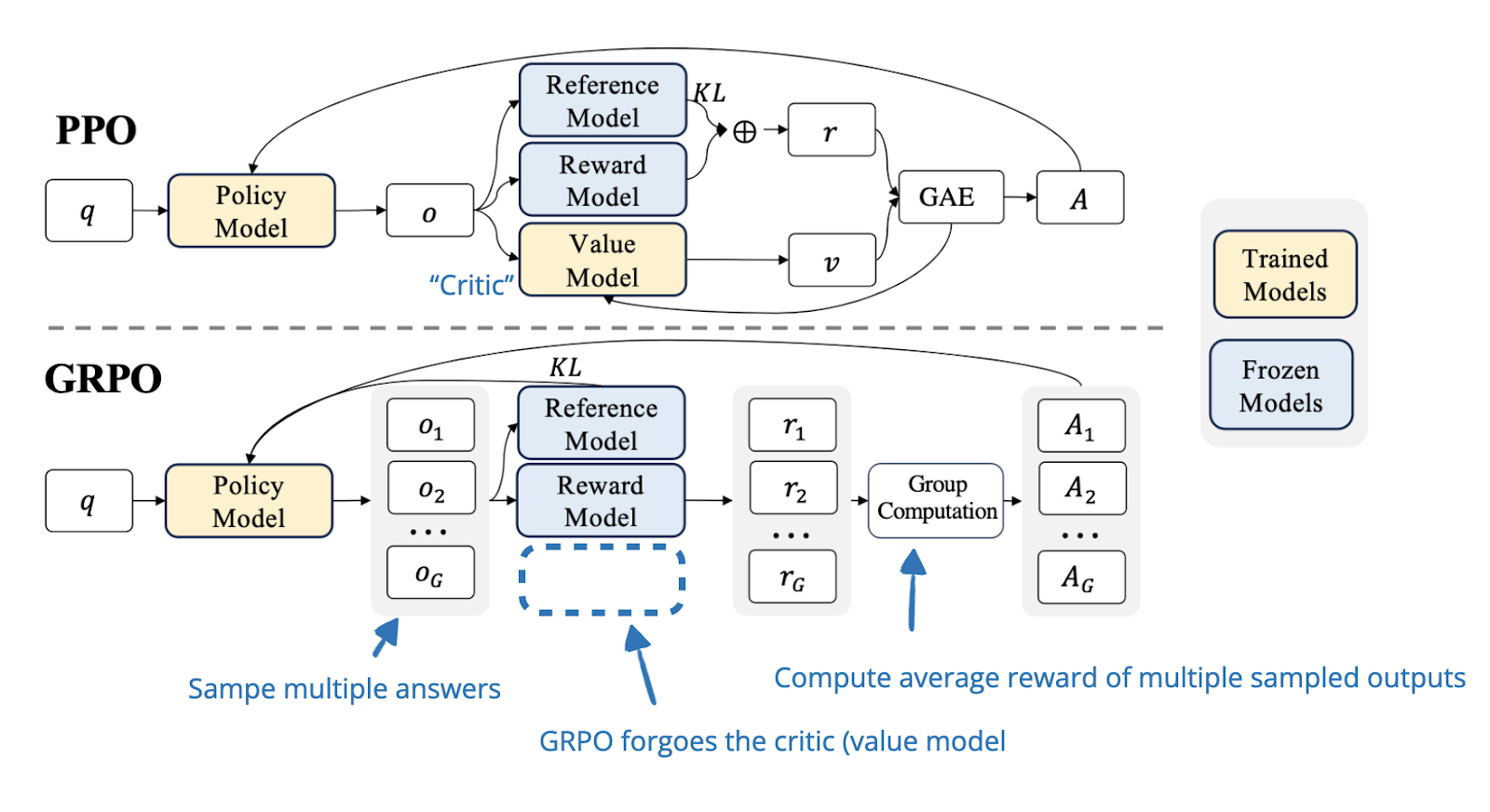

As mentioned before, PPO was the original algorithm used in RLHF. From a technical standpoint, it works perfectly fine in the RL pipeline that’s being used to develop reasoning models. However, what DeepSeek-R1 used for their RL pipeline is an algorithm called Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO), which was introduced in one of their earlier papers:

The DeepSeek team introduced GRPO as

a variant of Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) that enhances mathematical reasoning abilities while concurrently optimizing the memory usage of PPO.

So, the key motivation here is to improve computational efficiency.

The efficiency improvements are achieved by dropping the “critic” (value model), i.e., the LLM that computes the value function (i.e., the expected future reward).

Instead of relying on this additional model to compute the estimated reward to compute the advantages, GRPO takes a simpler approach: it samples multiple answers from the policy model itself and uses their relative quality to compute the advantages.

To illustrate the differences between PPO and GRPO, I borrowed a nice figure from the DeepSeekMath paper:

Ahead of AI is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Subscribe

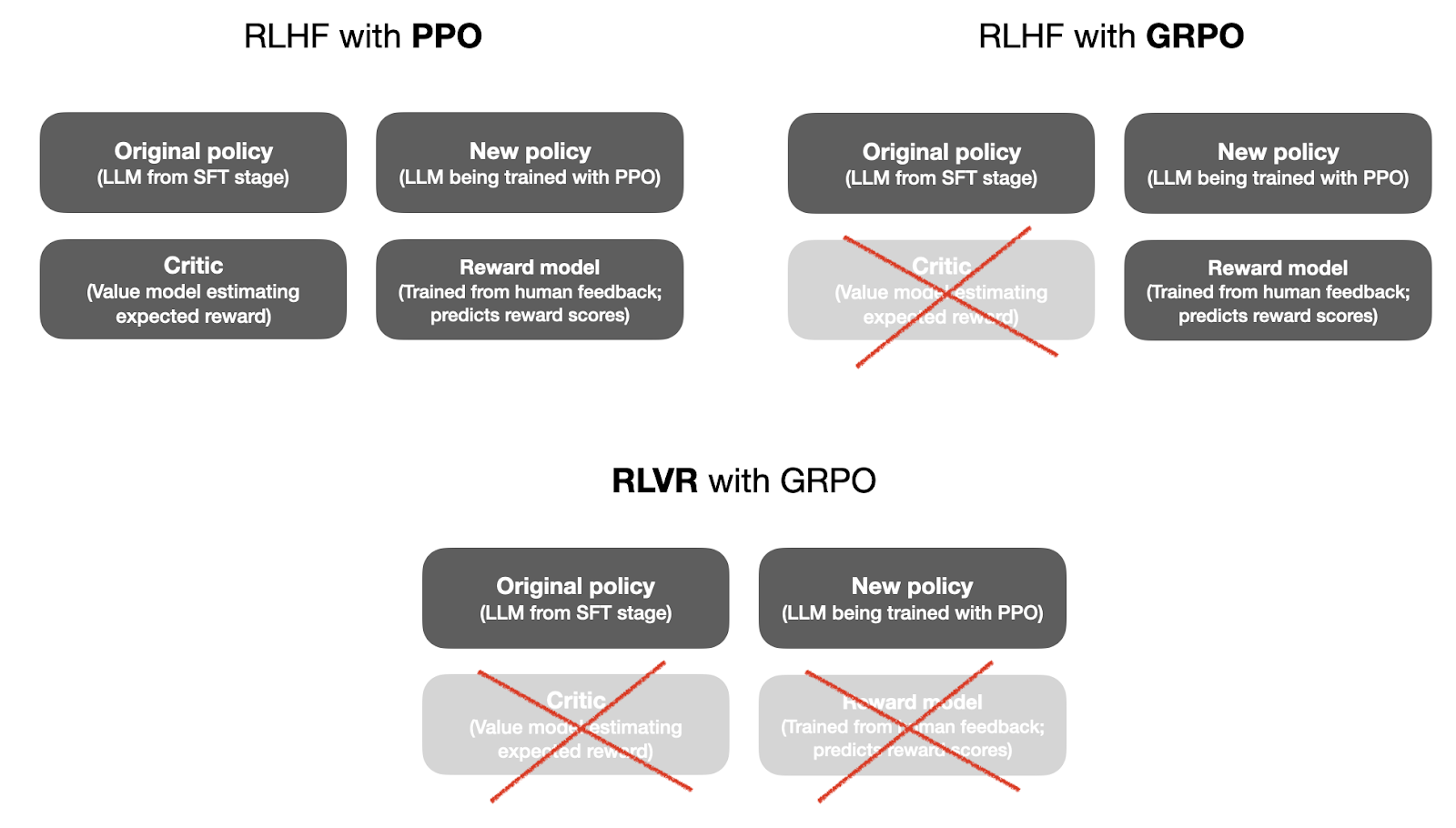

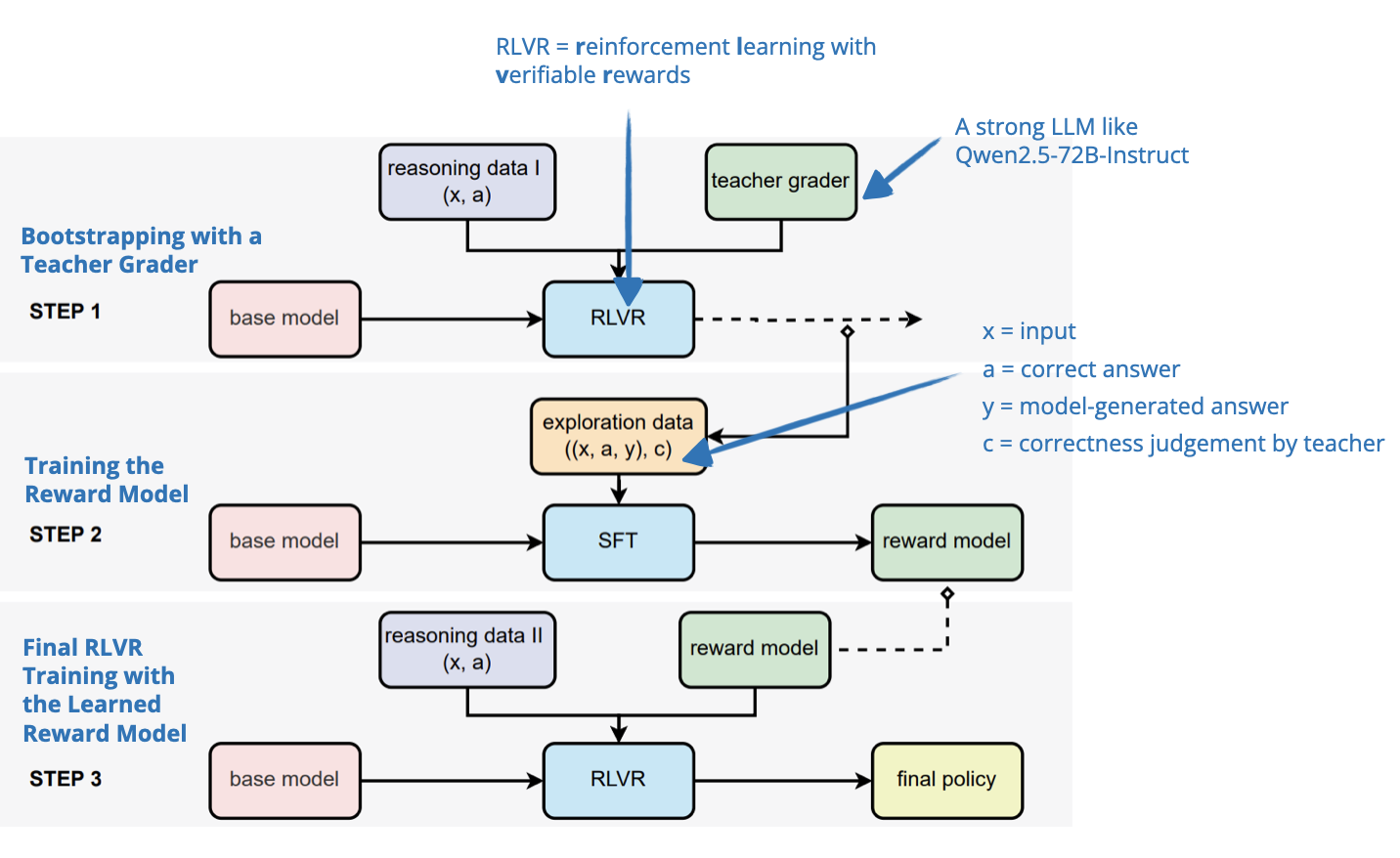

RL reward modeling: from RLHF to RLVR

So far, we looked at RLHF as a procedure, and we have introduced two reinforcement learning algorithms commonly used for it: PPO and GRPO.

But if RLHF is already a core part of the LLM alignment toolkit, what does any of this have to do with reasoning?

The connection between RLHF and reasoning comes from how the DeepSeek team applied a similar RL-based approach (with GRPO) to train the reasoning capabilities of their R1 and R1-Zero models.

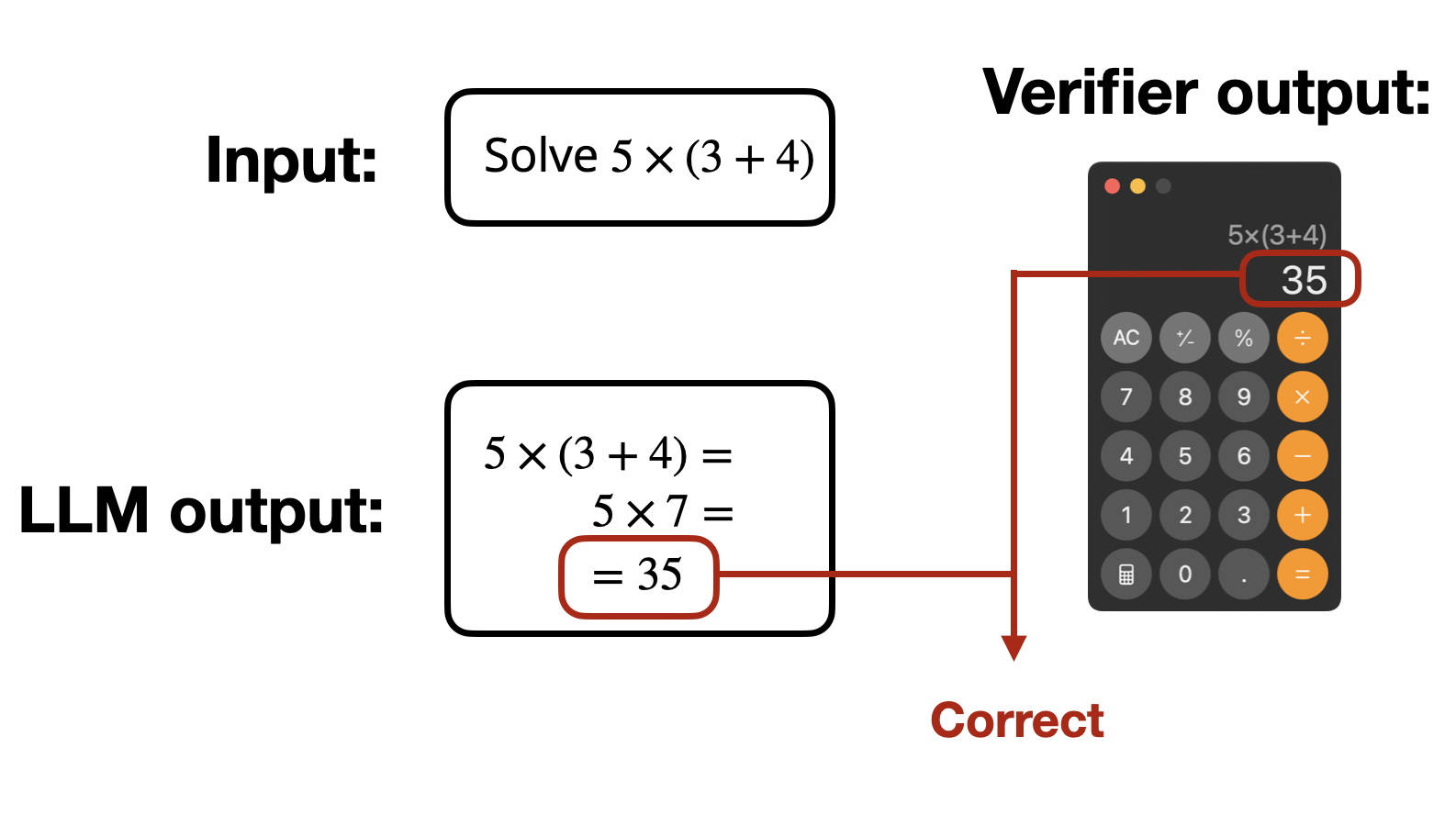

The difference is that instead of relying on human preferences and training a reward model, the DeepSeek-R1 team used verifiable rewards. This approach is called reinforcement learning with verifiable rewards (RLVR).

Again, it’s worth emphasizing: In contrast to standard RLHF, RLVR bypasses the need for a reward model.

So, rather than learning what counts as a “good” answer from human-labeled examples, the model gets direct binary feedback (correct or wrong) from a deterministic tool, such as symbolic verifiers or rule-based tools. Think calculators for math problems or compilers for code generation.

One motivation here is to avoid noisy or expensive human or learned rewards by using automatic correctness checks as supervision signals during RL. The other motivation is that by using “cheap” tools like calculators, we can replace the expensive reward model training and the reward model itself. Since the reward model is usually the whole pre-trained model (but with a regression head), RLVR is much more efficient.

So, in short, DeepSeek-R1 used RLVR with GRPO, which eliminates two expensive models in the training procedure: the reward model and the value model (critic), as illustrated in the figure below.

In the next section, I want to briefly go over the DeepSeek-R1 pipeline and discuss the different verifiable rewards that the DeepSeek team used.

How the DeepSeek-R1 reasoning models were trained

Now that we have clarified what RLHF and RLVR are, as well as PPO and GRPO, let’s briefly recap the main insights from the DeepSeek-R1 paper in the context of RL and reasoning.

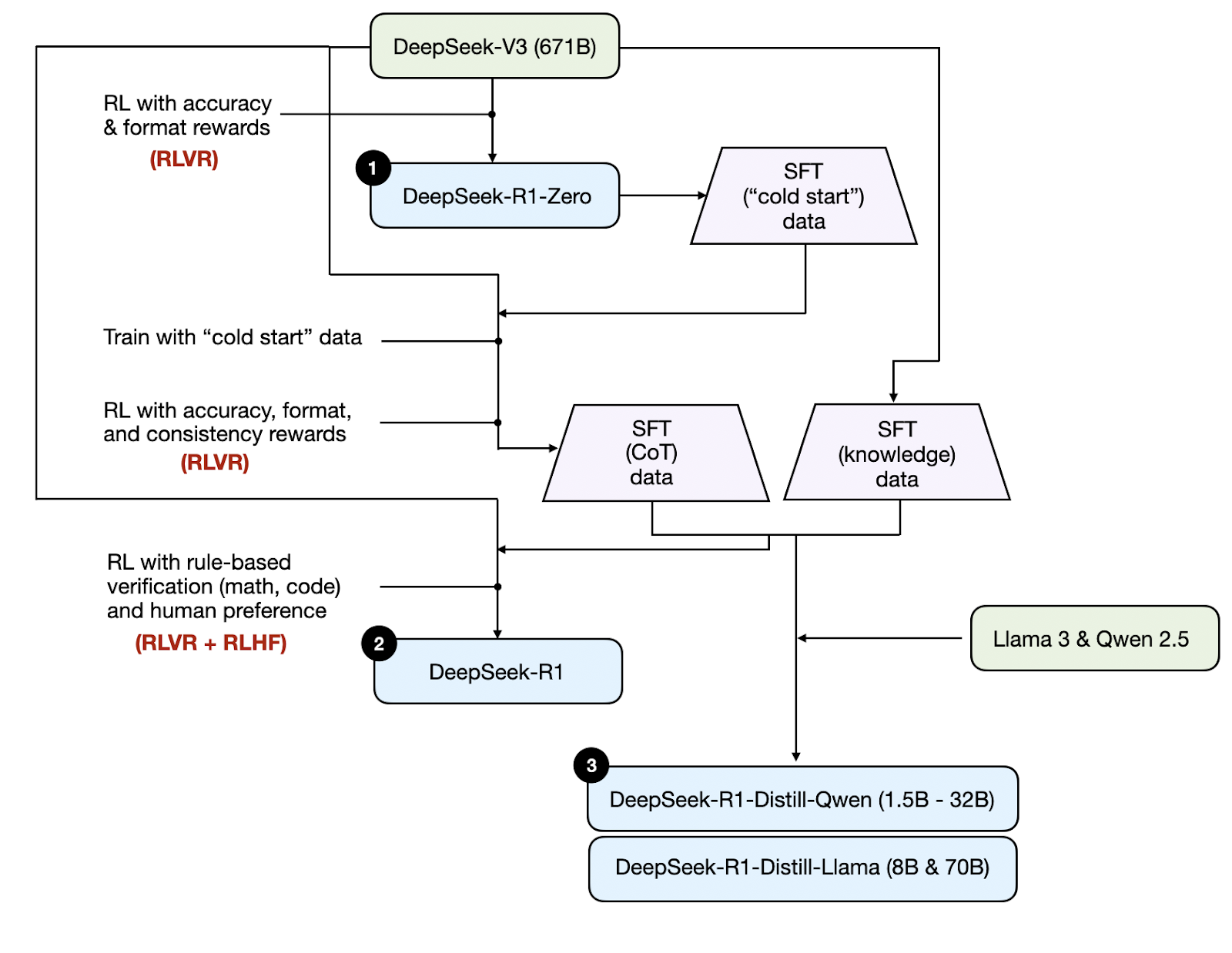

First, there were three types of models:

- DeepSeek-R1-Zero trained with pure RL

- DeepSeek-R1 trained with instruction fine-tuning (SFT) and RL

- DeepSeek-Distill variants created via instruction fine-tuning SFT without RL

I created a DeepSeek-R1 pipeline diagram to illustrate how these models relate to each other, as shown below.

DeepSeek-R1-Zero was trained using the verifiable rewards (RLVR) with GRPO, and this turned out to be sufficient for the model to exhibit reasoning abilities via intermediate-step generation. This showed that it’s possible to skip the SFT stage. The model improves its reasoning abilities through exploration instead of learning from examples.

DeepSeek-R1 is the flagship model, the one with the best performance. The difference compared to DeepSeek-R1-Zero is that they alternated instruction fine-tuning, RLVR, and RLHF.

DeepSeek-Distill variants are meant to be small and more easily deployable models; they were generated by instruction fine-tuning Llama 3 and Qwen 2.5 models using instruction data from the DeepSeek-R1 model. This approach didn’t use any RL for the reasoning part (however, RLHF was used to create the Llama 3 and Qwen 2.5 base models).

For more details on explaining the DeepSeek-R1 pipeline, please see my previous article “Understanding Reasoning LLMs”:

Understanding Reasoning LLMs

·

Feb 5

The main takeaway here is that the DeepSeek team didn’t use an LLM-based reward model to train DeepSeek-R1-Zero. Instead, they used rule-based rewards for the reasoning training of DeepSeek-R1-Zero and DeepSeek-R1:

We do not apply the outcome or process neural reward model in developing DeepSeek-R1-Zero, because we find that the neural reward model may suffer from reward hacking in the large-scale reinforcement learning process […]

To train DeepSeek-R1-Zero, we adopt a rule-based reward system that mainly consists of two types of rewards:

(1) Accuracy rewards: The accuracy reward model evaluates whether the response is correct. For example, in the case of math problems with deterministic results, the model is required to provide the final answer in a specified format (e.g., within a box), enabling reliable rule-based verification of correctness. Similarly, for LeetCode problems, a compiler can be used to generate feedback based on predefined test cases.

(2) Format rewards: In addition to the accuracy reward model, we employ a format reward model that enforces the model to put its thinking process between ‘

' and ' ’ tags.

Lessons from recent RL papers on training reasoning models

I realize that the introduction (i.e., everything up to this point) turned out to be much longer than I expected. Nonetheless, I think that this lengthy introduction is perhaps necessary to put the following lessons into context.

After going through a large number of recent papers on reasoning models last month, I have put together a summary of the most interesting ideas and insights in this section. (References like “[1]” point to the corresponding papers listed at the end of the article.)

1. Reinforcement learning further improves distilled models

The original DeepSeek-R1 paper demonstrated clearly that supervised fine-tuning (SFT) followed by reinforcement learning (RL) outperforms RL alone.

Given this observation, it’s intuitive that additional RL should further improve distilled models (as distilled models essentially represent models trained via SFT using reasoning examples generated by a larger model.)

Indeed, the DeepSeek team observed this phenomenon explicitly:

Additionally, we found that applying RL to these distilled models yields significant further gains. We believe this warrants further exploration and therefore present only the results of the simple SFT-distilled models here.

Several teams independently verified these observations:

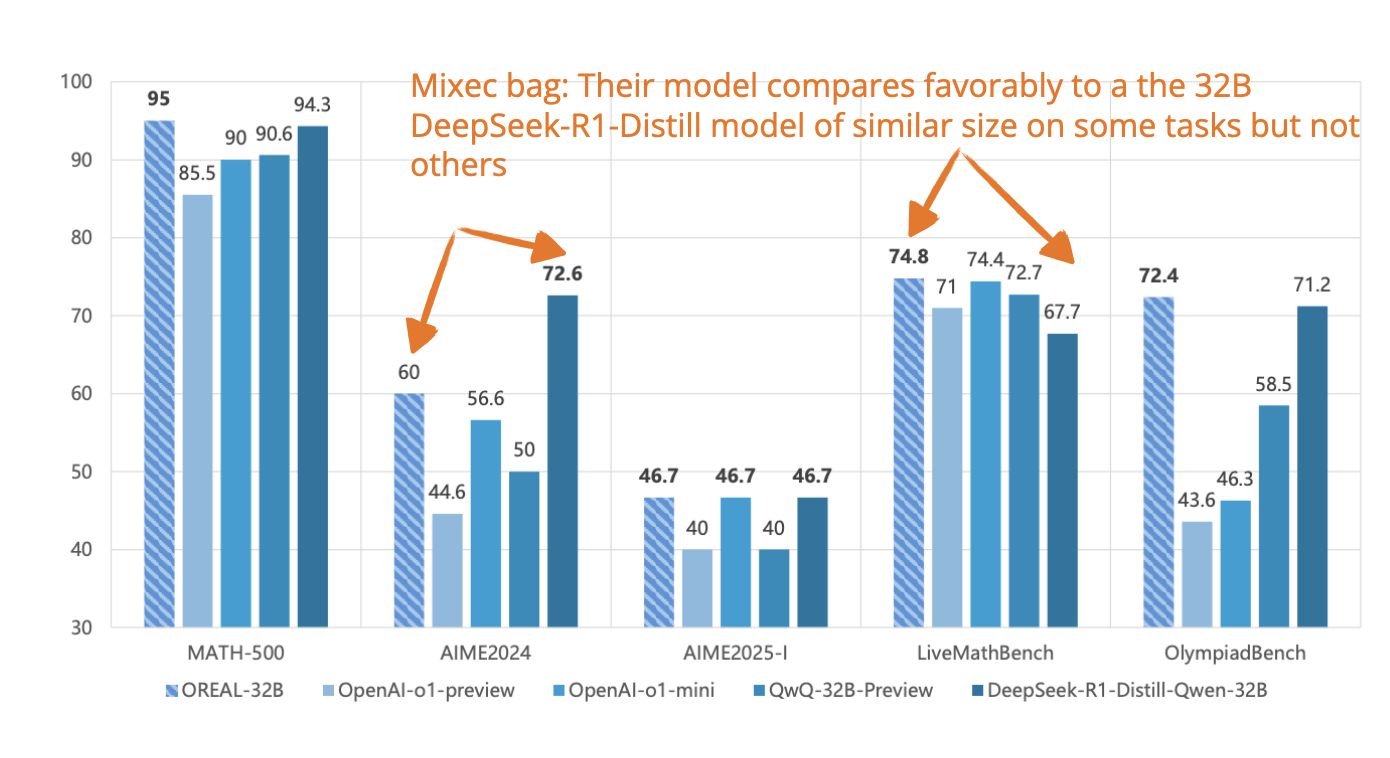

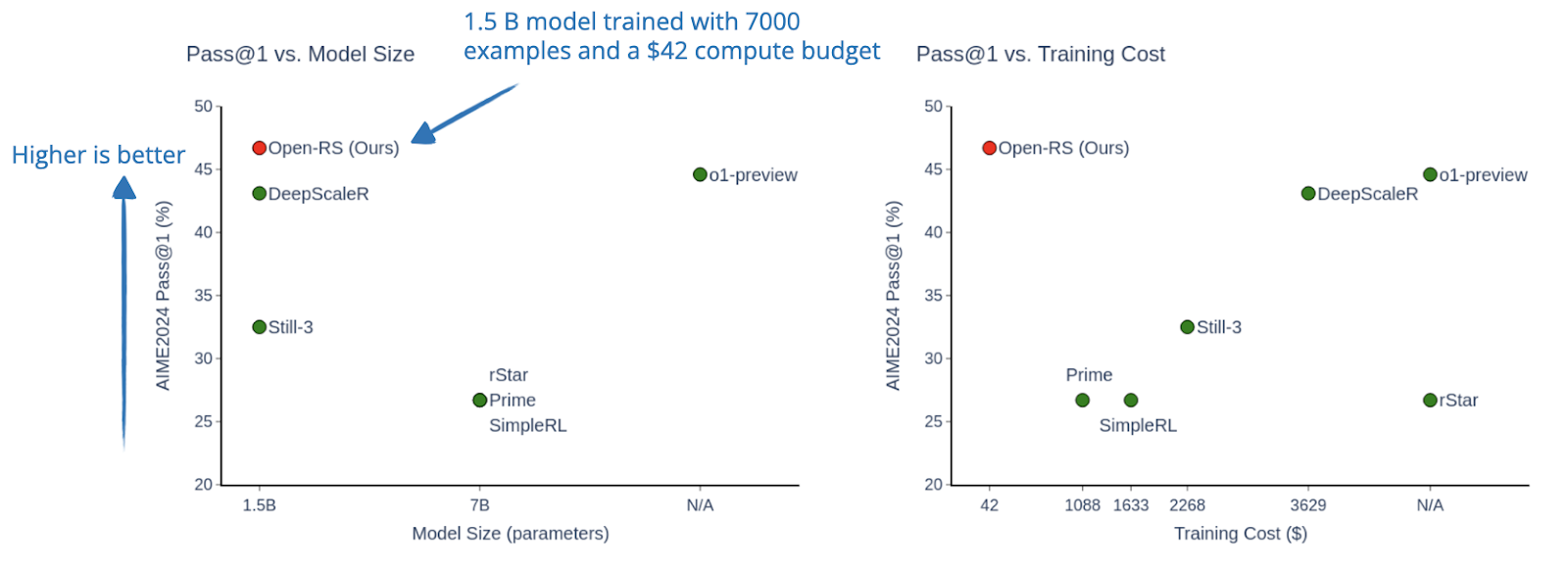

- [8] Using the 1.5B DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Qwen model, researchers demonstrated substantial performance improvements from RL fine-tuning with just 7,000 examples and a modest $42 compute budget. Impressively, this small model surpassed OpenAI’s o1-preview on the AIME24 math benchmark.

- [15] However, another team cautioned that these gains might not always be statistically significant. This suggests that, although RL can improve smaller distilled models, the benchmark results might sometimes be overstating the improvements.

2. The problem of long incorrect answers

I previously mentioned that RL with verifiable rewards (RLVR) does not strictly require the GRPO algorithm; DeepSeek’s GRPO simply happens to be efficient and to perform well.

However, [12] showed that vanilla PPO paired with a basic binary correctness reward was sufficient to scale models in reasoning capability and response length.

More interestingly, both PPO and GRPO have a length bias. And several papers explored methods to tackle excessively long incorrect answers:

- [14] Provided an analysis illustrating how PPO inadvertently favors longer responses due to mathematical biases in loss calculations; GRPO may suffer from the same issue.

- As a follow-up to the statement above, [7] [10] specifically identified length and difficulty-level biases in GRPO. The modified variant “Dr. GRPO” simplifies advantage calculations by removing length and standard deviation normalization, providing clearer training signals.

- [1] Explicitly penalized lengthy incorrect answers in GRPO while rewarding concise, correct ones.

- [3] [6] Didn’t directly control response length in GRPO but found token-level rewards beneficial, allowing models to better focus on critical reasoning steps.

- [5] Introduced explicit penalties in GRPO for responses exceeding specific lengths, enabling precise length control during inference.

3. Emergent abilities from RL

Beyond “AHA” moments mentioned in the DeepSeek-R1 paper, RL has been shown to induce valuable self-verification and reflective reasoning capabilities in models [2] [9]. Interestingly, similar to the AHA moment, these capabilities emerged naturally during training without explicit instruction.

[1] Showed that extending context lengths (up to 128k tokens) further improves the model’s self-reflection and self-correction capabilities.

4. Generalization beyond specific domains

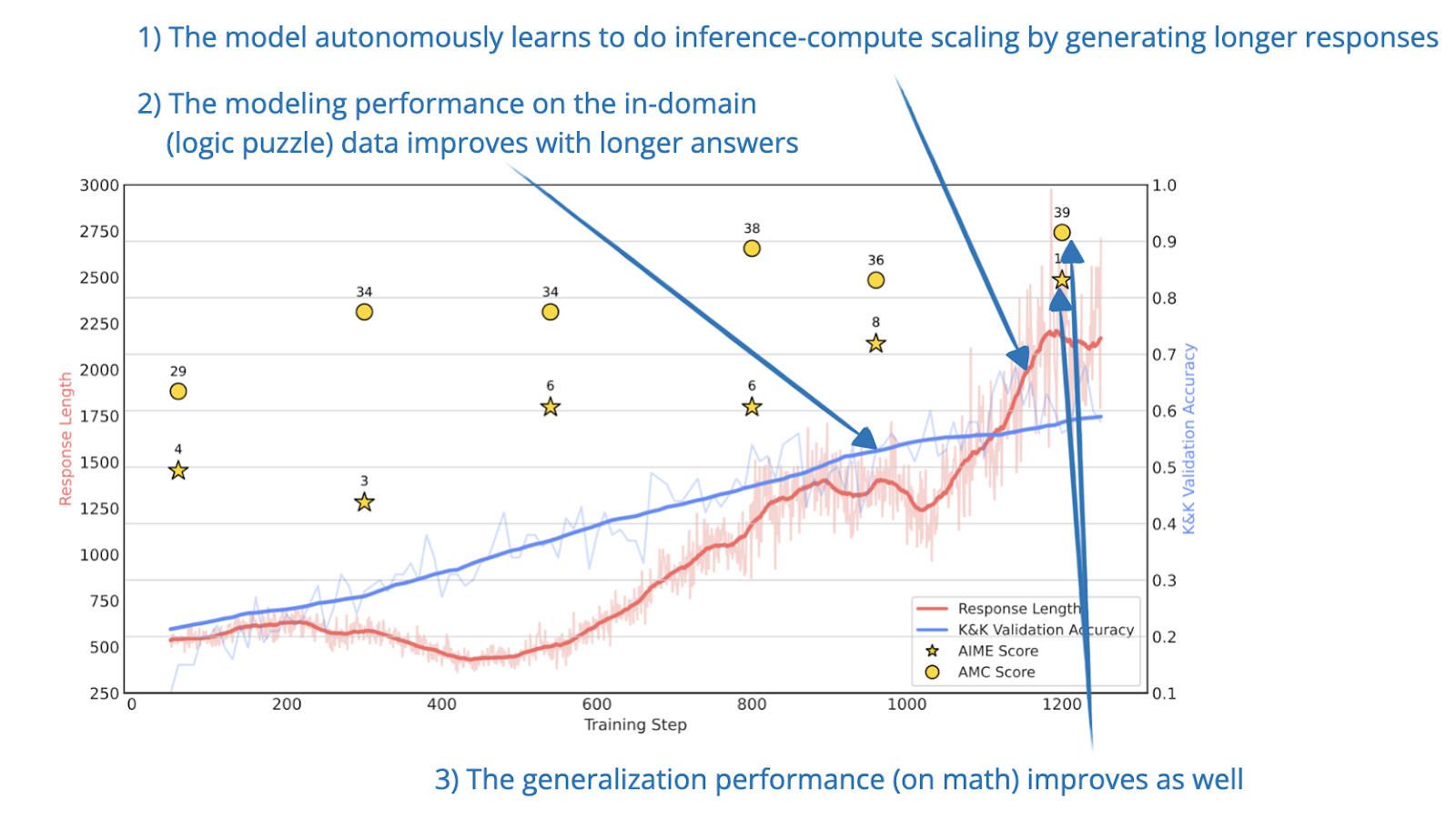

Most research efforts so far has focused on reasoning tasks in math or coding contexts. However, [4] demonstrated successful generalization by training models on logic puzzles. And models trained on logic puzzles also achieved strong performance in mathematical reasoning tasks. This is evidence for RL’s ability to induce general reasoning behaviors independent of specific domain knowledge.

5. Extensions to broader domains

As a follow-up to the section above, another interesting insight [11] is that reasoning capabilities can naturally extend beyond structured domains like math, code, and logic.

Models successfully applied reasoning to areas including medicine, chemistry, psychology, economics, and education, leveraging generative soft-scoring methods to effectively handle free-form answers.

Notable next steps for reasoning models include:

- Integrating existing reasoning models (e.g., o1, DeepSeek-R1) with capabilities such as external tool use and retrieval-augmented generation (RAG); the just-released o3 model from Open AI paves the way here

- Speaking of tool-use and search, [9] showed that giving reasoning models the ability to search induces behaviors such as self-correction and robust generalization across benchmarks, despite minimal training datasets.

Based on the hoops DeepSeek-R1 team went through in terms of maintaining the performance on knowledge-based tasks, I believe adding search abilities to reasoning models is almost a no-brainer.

6. Is reasoning solely due to RL?

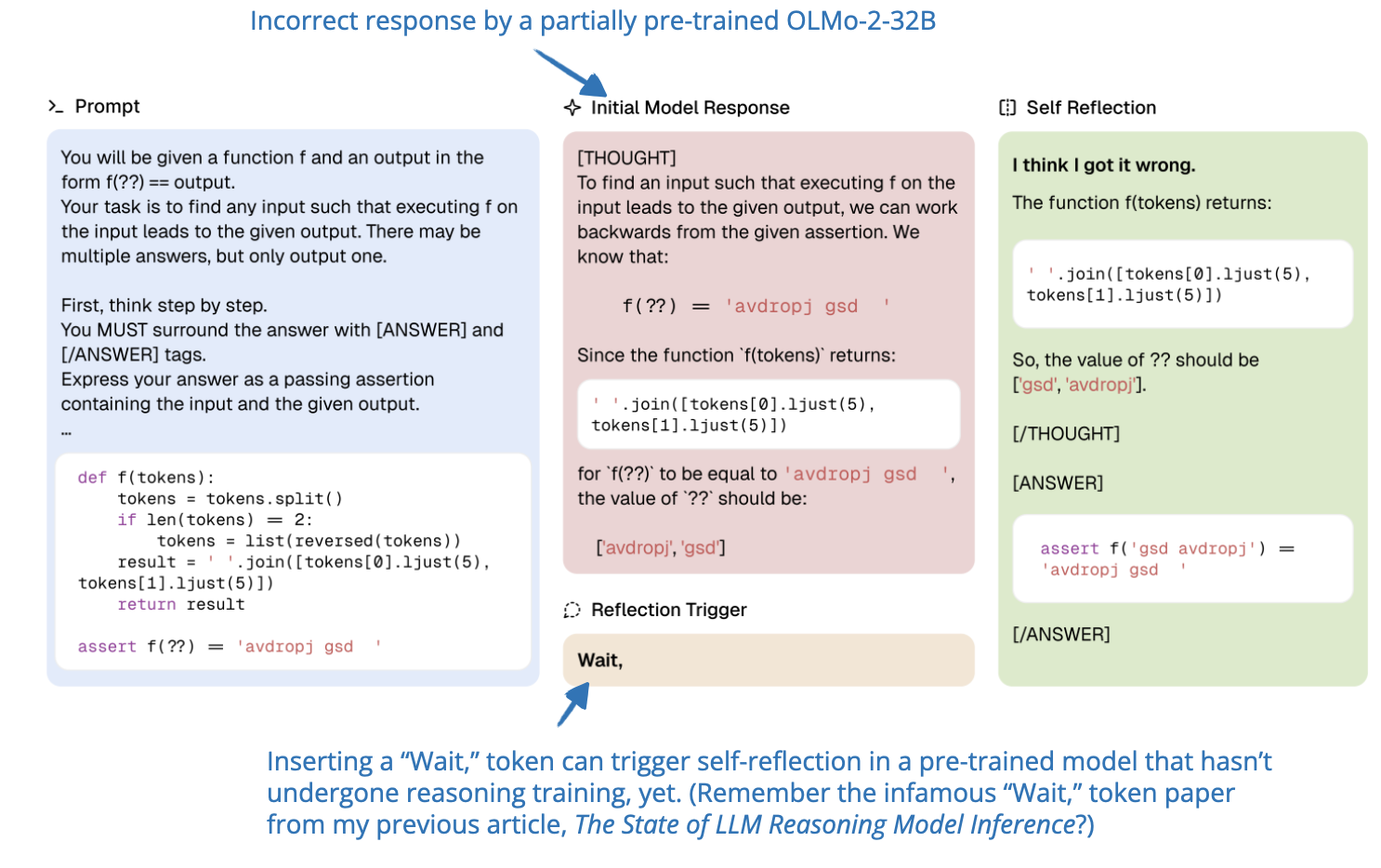

The fundamental claim behind DeepSeek-R1 (and R1-Zero) is that RLVR explicitly induces reasoning capabilities. However, recent findings [10] suggest that reasoning behaviors, including the “Aha moment,” might already be present in base models due to pre-training on extensive chain-of-thought data.

My recent comparisons between DeepSeek V3 base and R1 reinforce this observation, as the updated base model also demonstrates reasoning-like behaviors. For instance, the comparison between the original V3 and R1 models clearly shows the difference between a non-reasoning and a reasoning model:

However, this is no longer true when comparing the updated V3 base model to R1:

Additionally, [13] identified that self-reflection and self-correction behaviors emerge progressively throughout pre-training across various domains and model sizes. This further complicates the attribution of reasoning capabilities solely to RL methods.

Perhaps the conclusion is that RL definitely turns simple base models into reasoning models. However, it’s not the only way to induce or improve reasoning abilities. As the DeepSeek-R1 team showed, distillation also improves reasoning. And since distillation, in this paper, meant instruction fine-tuning on chain-of-thought data, it’s likely that pre-training on data that includes chain-of-thought data induces these abilities as well. (As I explained in my book through hands-on code, pre-training and instruction fine-tuning are based on the same next-token prediction task and loss functions, after all.)

Noteworthy research papers on training reasoning models

After reading through a large number of reasoning papers last month, I tried to summarize the most interesting takeaways in the previous section. However, for those who are curious about the sources with a bit more detail, I also listed 15 relevant papers in this section below as an optional read. (For simplicity, the following summaries are sorted by date.)

Please note that this list is also not comprehensive (I capped it at 15), as this article is already more than too long!

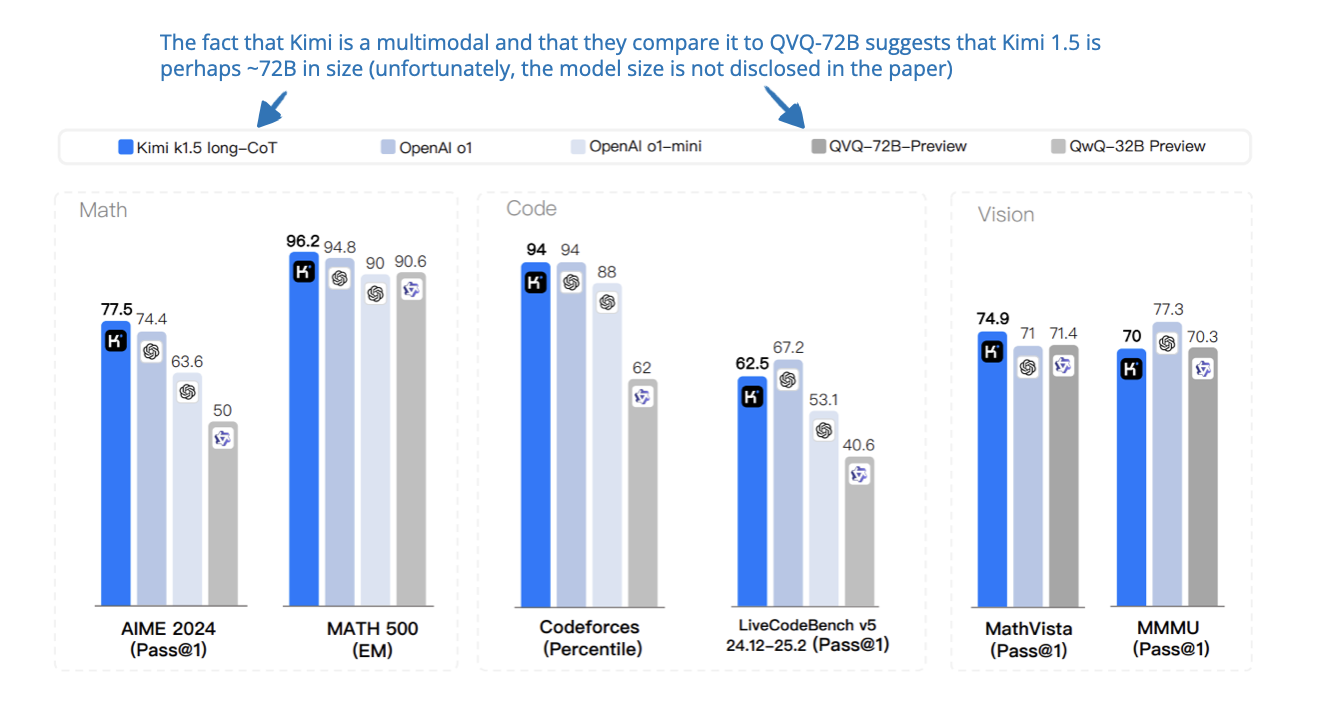

[1] Scaling Reinforcement Learning (And Context Length)

📄 22 Jan, Kimi k1.5: Scaling Reinforcement Learning with LLMs, https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.12599

It’s interesting that this paper came out the same day as the DeepSeek-R1 paper! Here, the authors showcase a multi-modal LLM trained with RL. Similar to DeepSeek-R1, they didn’t use process reward models (PRMs) but employed verifiable rewards. A PRM is a type of reward model used in RL (especially in LLM training) that evaluates not just the final answer but also the reasoning steps that led to it.

Another key idea here is that scaling the context length (up to 128k tokens) helps the model plan, reflect, and self-correct during reasoning. So, in addition to the correctness reward that is similar to DeepSeek-R1 they also have a length reward. Specifically, they promote shorter correct responses, and incorrect long answers get penalized more.

And they propose a method called long2short to distill these long-chain-of-thought skills into more efficient short-CoT models. (It does this by distilling shorter correct responses from the long-CoT model using methods like model merging, shortest rejection sampling, DPO, and a 2nd round of RL with stronger length penalties.)

[2] Competitive Programming with Large Reasoning Models

📄 3 Feb, Competitive Programming with Large Reasoning Models, https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.06807

This paper from OpenAI evaluates their o-models (like o1, o1-ioi, and o3) on competitive programming tasks. While it doesn’t go into the technical details of how RL was applied, it still offers some interesting takeaways.

First, the models were trained using outcome-based RL, rather than process-based reward models. This is similar to approaches like DeepSeek-R1 and Kimi.

One of the interesting findings is that o3 can learn its own test-time (i.e., inference-time scaling) strategies. For example, it often writes a simple brute-force version of a problem (something that trades efficiency for correctness) and then uses it to verify the outputs of its more optimized solution. This kind of strategy wasn’t hand-coded; the model figured it out on its own.

So overall, the paper argues that scaling general-purpose RL allows models to develop their own reasoning and verification methods, without needing any human heuristics or domain-specific inference pipelines. In contrast, other (earlier) models like o1-ioi relied on handcrafted test-time strategies like clustering thousands of samples and reranking them, which required a lot of manual design and tuning.

[3] Exploring the Limit of Outcome Reward

📄 10 Feb, Exploring the Limit of Outcome Reward for Learning Mathematical Reasoning, https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.06781

This paper explores how far RL with just binary “correct” or “wrong” feedback (like in DeepSeek-R1) can go for solving math problems. To do this, they start by using Best-of-N sampling to collect positive examples and apply behavior cloning on them, which they show is theoretically enough to optimize the policy.

To deal with the challenge of sparse rewards (especially when long chains of thought include partially correct steps) they add a token-level reward model that learns to assign importance weights to different parts of the reasoning. This helps the model focus on the most critical steps when learning and improves the overall performance.

[4] LLM Reasoning with Rule-Based Reinforcement (On Logic Data)

📄 20 Feb, Logic-RL: Unleashing LLM Reasoning with Rule-Based Reinforcement Learning, https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.14768

DeepSeek-R1 focused on math and code tasks. This paper trains a 7B model using logic puzzles as the main training data.

The researchers adopt a similar rule-based RL setup as DeepSeek-R1 but make several adjustments:

-

They introduce a strict format reward that penalizes shortcuts and ensures the model separates its reasoning from its final answer using

and tags. -

They also use a system prompt that explicitly tells the model to first think through the problem step-by-step before giving the final answer.

Even with only 5K synthetic logic problems, the model develops good reasoning skills that generalize well to harder math benchmarks like AIME and AMC.

This is particularly interesting because it shows that logic-based RL training can teach models to reason in ways that transfer beyond the original domain.

[5] Controlling How Long A Reasoning Model Thinks

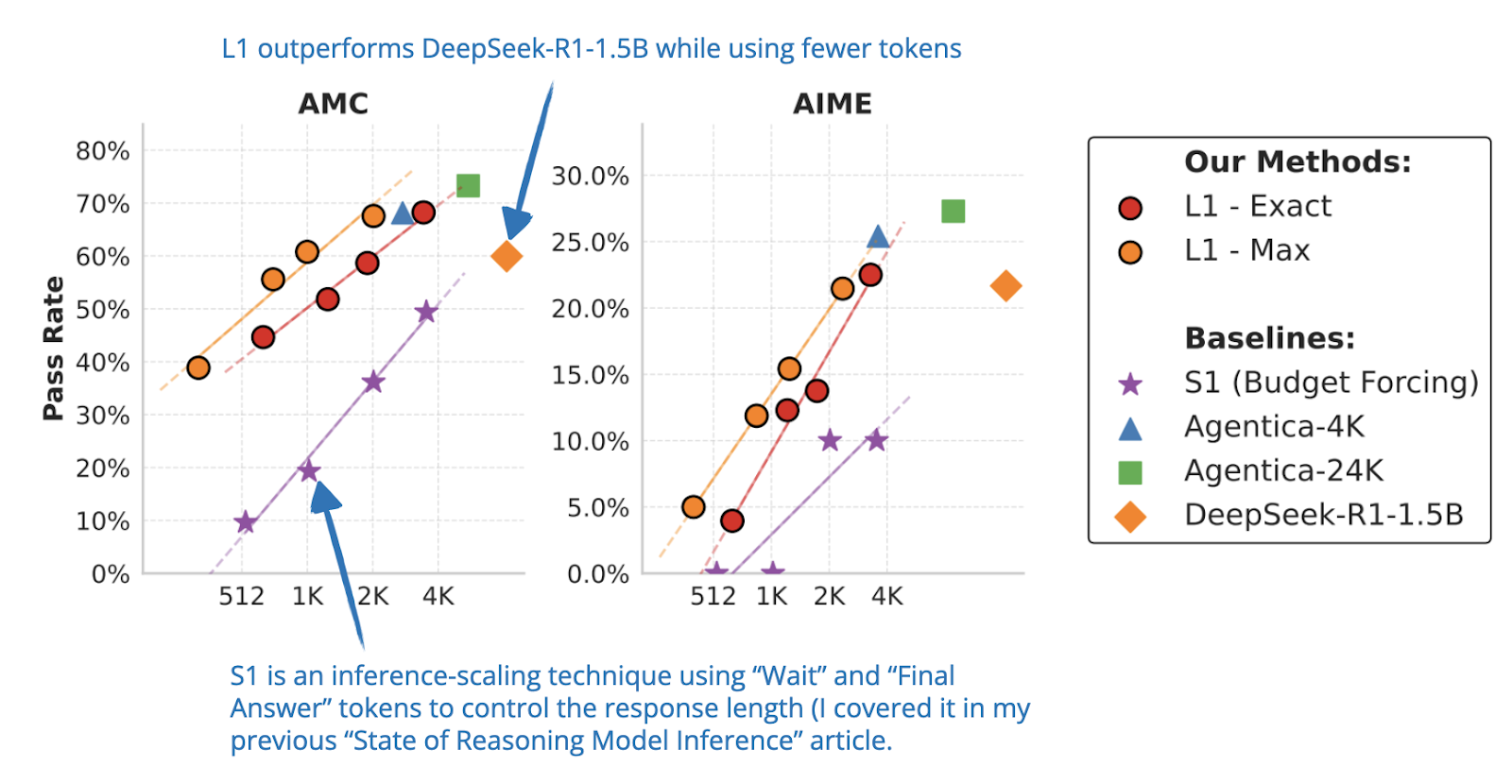

📄 6 Mar, L1: Controlling How Long A Reasoning Model Thinks With Reinforcement Learning, https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.04697

One hallmark of reasoning models is that they tend to generate longer outputs because of chain-of-thought reasoning. But by default, there is no explicit way to control how long the responses are.

This paper introduces Length Controlled Policy Optimization (LCPO), a simple reinforcement learning method that helps models to adhere to user-specified length constraints while still optimizing for accuracy.

In short, LCPO is similar to GRPO, i.e., “GRPO + Custom Reward for Length Control” implemented as

reward = reward_correctness - α * |target_length - actual_length|

where the target length is provided as part of the user prompt. This LCPO method above encourages the model to adhere to the provided target length exactly.

In addition, they also introduce an LCPO-Max variant, which, instead of encouraging the model to match the target length exactly, encourages the model to stay below a maximum token length:

reward = reward_correctness * clip(α * (target_length - actual_length) + δ, 0, 1)

The authors train a 1.5B model called L1 using LCPO, which can adjust its output length based on the prompt. This lets users trade-off between accuracy and compute, depending on the task. Interestingly, the paper also finds that these long-chain models actually become surprisingly good at short reasoning too, even outperforming much larger models like GPT-4o at the same token lengths.

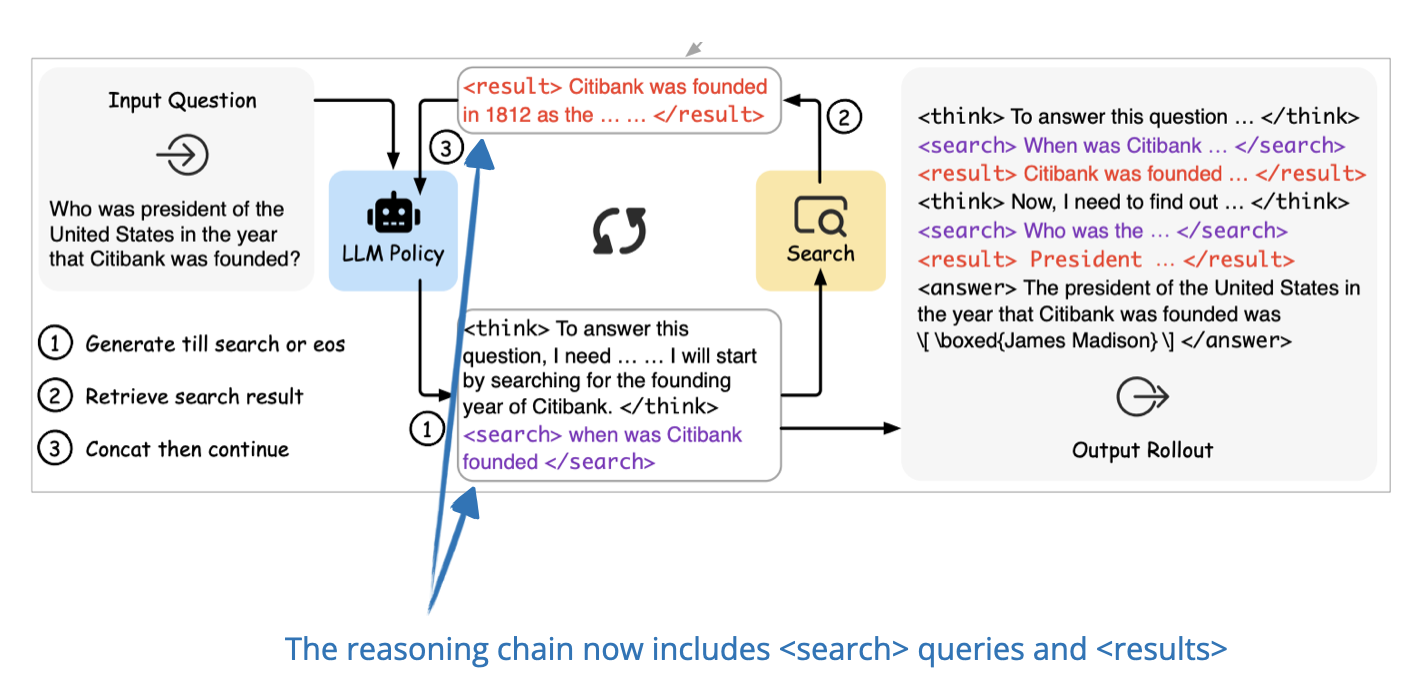

[6] Incentivizing the Search Capability in LLMs

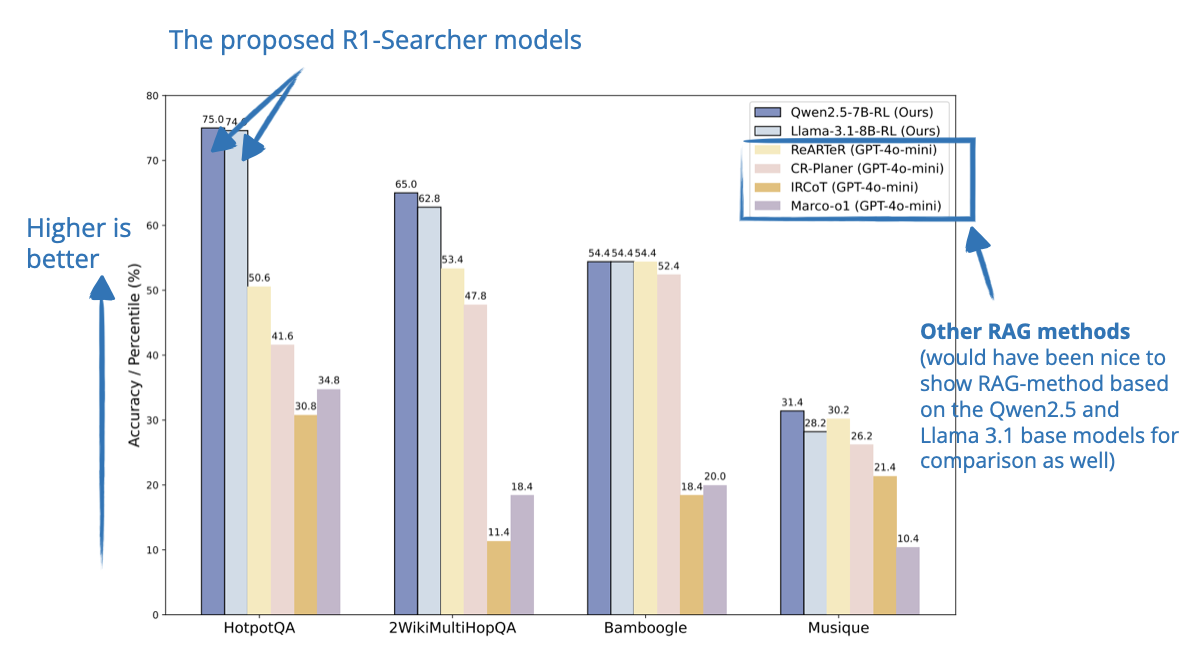

📄 10 Mar, R1-Searcher: Incentivizing the Search Capability in LLMs via Reinforcement Learning, https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.05592

Reasoning models like DeepSeek-R1 that have been trained with RL rely on their internal knowledge. The authors here focus on improving these models on knowledge-based tasks that require more time-sensitive or recent information by adding access to external search systems.

So, this paper improves these models by teaching them to use external search systems during the reasoning process. Instead of relying on test-time strategies or supervised training, the authors use a two-stage reinforcement learning method that helps the model learn how and when to search on its own. The model first learns the search format, and then learns how to use search results to find correct answers.

[7] Open-Source LLM Reinforcement Learning at Scale

📄 18 Mar, DAPO: An Open-Source LLM Reinforcement Learning System at Scale, https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.14476

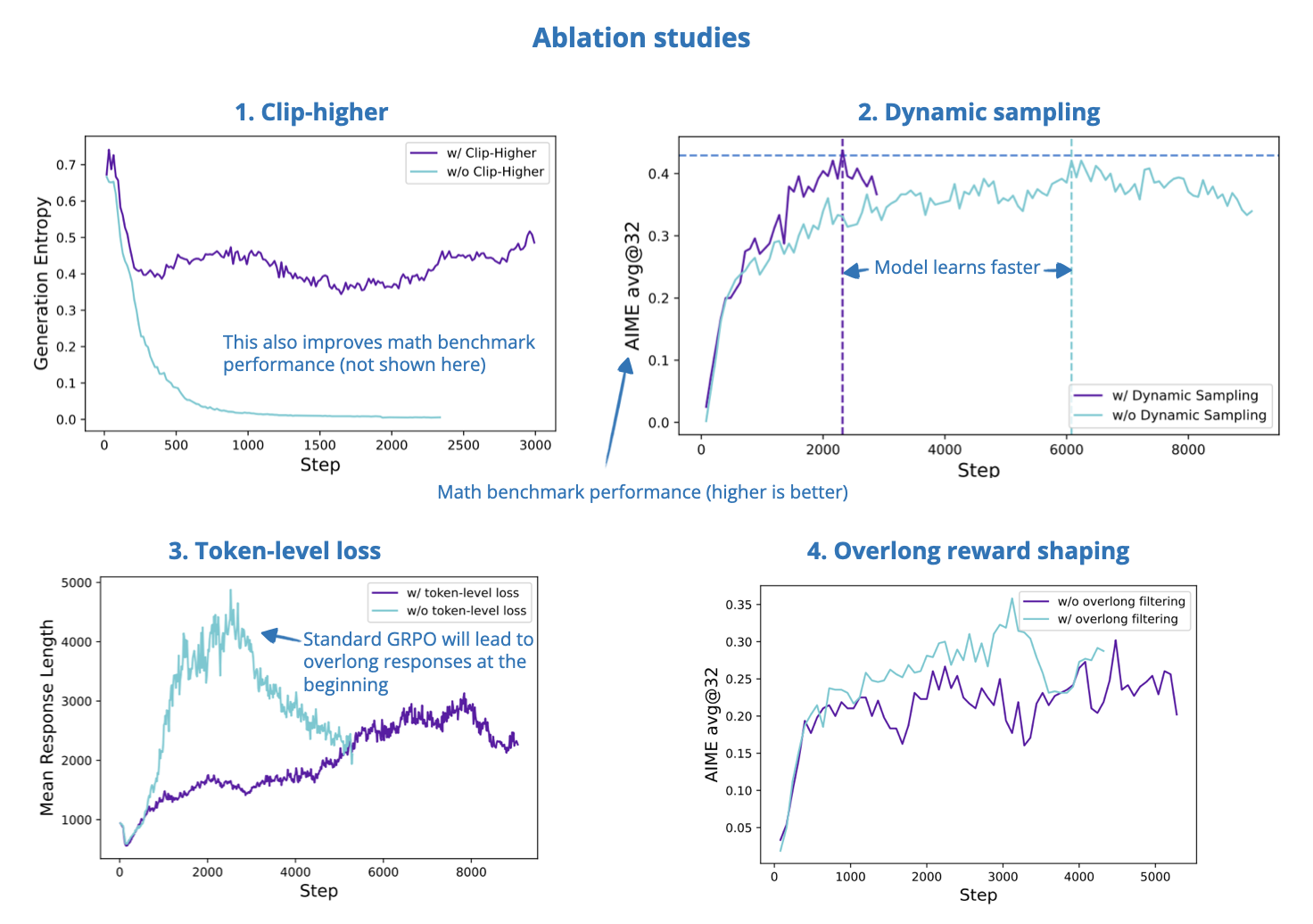

While this paper is mainly about developing a DeepSeek-R1-like training pipeline and open-sourcing it, it also proposes interesting improvements to the GRPO algorithm that was used in DeepSeek-R1 training.

-

Clip-higher: Increases the upper bound of the PPO clipping range to encourage exploration and prevent entropy collapse during training.

-

Dynamic sampling: Improves training efficiency by filtering out prompts where all sampled responses are either always correct or always wrong.

-

Token-level policy gradient loss: moves from sample-level to token-level loss calculation so that longer responses can have more influence on the gradient update.*

-

Overlong reward shaping: Adds a soft penalty for responses that get truncated for being too long, which reduces reward noise and helps stabilize training.

* Standard GRPO uses a sample-level loss calculation. This involves first averaging the loss over the tokens for each sample and then averaging the loss over the samples. Since the samples have equal weight, the tokens in samples with longer responses may disproportionally contribute less to the overall loss. At the same time, researchers observed that longer responses often contain gibberish before the final answer, and this gibberish wouldn’t be sufficiently penalized in the original GRPO sample-level loss calculation.

[8] Reinforcement Learning for Reasoning in Small LLMs

📄 20 Mar, Reinforcement Learning for Reasoning in Small LLMs: What Works and What Doesn’t, https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.16219

The original DeepSeek-R1 paper showed that when developing small(er) reasoning models, distillation gives better results than pure RL. In this paper, researchers follow up on this and investigate ways to improve small, distilled reasoning models further with RL.

So, using the 1.5B DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Qwen model, they find that with only 7000 training examples and a $42 compute budget, RL fine-tuning can lead to strong improvements. In this case, the improvements are enough to outperform OpenAI’s o1-preview on the AIME24 math benchmark, for example.

Furthermore, there were 3 interesting learnings in that paper:

-

Small LLMs can achieve fast reasoning improvements within the first 50–100 training steps using a compact, high-quality dataset. But the performance quickly drops if training continues too long, mainly due to length limits and output instability.

-

Mixing easier and harder problems helps the model produce shorter, more stable responses early in training. However, performance still degrades over time.

-

Using a cosine-shaped reward function helps control output length more effectively and improves training consistency. But this slightly reduces peak performance compared to standard accuracy-based rewards.

[9] Learning to Reason with Search

📄 25 Mar, ReSearch: Learning to Reason with Search for LLMs via Reinforcement Learning, https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.19470

The ReSearch framework proposed in this paper extends the RL method from the DeepSeek-R1 paper to include search results as part of the reasoning process. The model learns when and how to search based on its ongoing reasoning chain, and it then uses the retrieved information for the next steps of reasoning.

This is all done without supervised data on reasoning steps. The researchers also show that this approach can lead to useful behaviors like self-correction and reflection, and that it generalizes well across multiple benchmarks despite being trained on just one dataset.

PS: How does this method differ from the R1-Searcher discussed earlier?

R1-Searcher uses a two-stage, outcome-based reinforcement learning approach. In the first stage, it teaches the model how to invoke external retrieval; in the second, it learns to use the retrieved information to answer questions.

ReSearch, in contrast, integrates search directly into the reasoning process. It trains the model end-to-end using reinforcement learning, without any supervision on reasoning steps. Behaviors such as reflecting on incorrect queries and correcting them emerge naturally during training here.

[10] Understanding R1-Zero-Like Training

📄 26 Mar, Understanding R1-Zero-Like Training: A Critical Perspective, https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.20783

This paper investigates why DeepSeek-R1-Zero’s pure RL approach works to improve reasoning.

The authors find that some base models like Qwen2.5 already show strong reasoning and even the “Aha moment” without any RL. So the “Aha moment” might not be induced by RL, but instead inherited from pre-training. This challenges the idea that RL alone is what creates deep reasoning behaviors.

The paper also identifies two biases in GRPO:

-

Response-length bias: GRPO divides the advantage by the length of the response. This makes long incorrect answers get smaller penalties, so the model learns to generate longer bad answers.

-

Difficulty-level bias: GRPO also normalizes by the standard deviation of rewards for each question. Easy or hard questions (with low reward variance) get overweighted.

To fix this, the authors introduce Dr. GRPO, which is a modification of standard GRPO. Here, they get rid of the response length normalization in the advantage computation. Also, they get rid of the question-level standard deviation. This will result in more efficient training and fewer unnecessary long answers. Especially if the model is wrong, generating a long answer is no longer encouraged.

[11] Expanding RL with Verifiable Rewards Across Diverse Domains

📄 31 Mar, Crossing the Reward Bridge: Expanding RL with Verifiable Rewards Across Diverse Domains, https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.23829

DeepSeek-R1 and most other reasoning models that followed focused on reward signals from easily verifiable domains like code and math. This paper explores how to extend these methods to more complex areas like medicine, chemistry, psychology, economics, and education, where answers are usually free-form and harder to verify (beyond a simple correct/incorrect).

The authors find that using expert-written reference answers makes evaluation more feasible than expected, even in these broader domains. To provide reward signals, they introduce a generative, soft-scoring method without needing heavy domain-specific annotation.

[12] Scaling Up Reinforcement Learning (With a Simple Setup)

📄 31 Mar, Open-Reasoner-Zero: An Open Source Approach to Scaling Up Reinforcement Learning on the Base Model, https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.24290

In this paper, the authors explore a minimalist reinforcement learning setup for training LLMs on reasoning tasks. They use vanilla PPO instead of GRPO (which was used in DeepSeek-R1-Zero) and skip the usual KL regularization commonly included in RLHF pipelines.

Interestingly, they find that this simple setup (vanilla PPO and a basic binary reward function based on answer correctness) is sufficient to train models that scale up in both reasoning performance and response length.

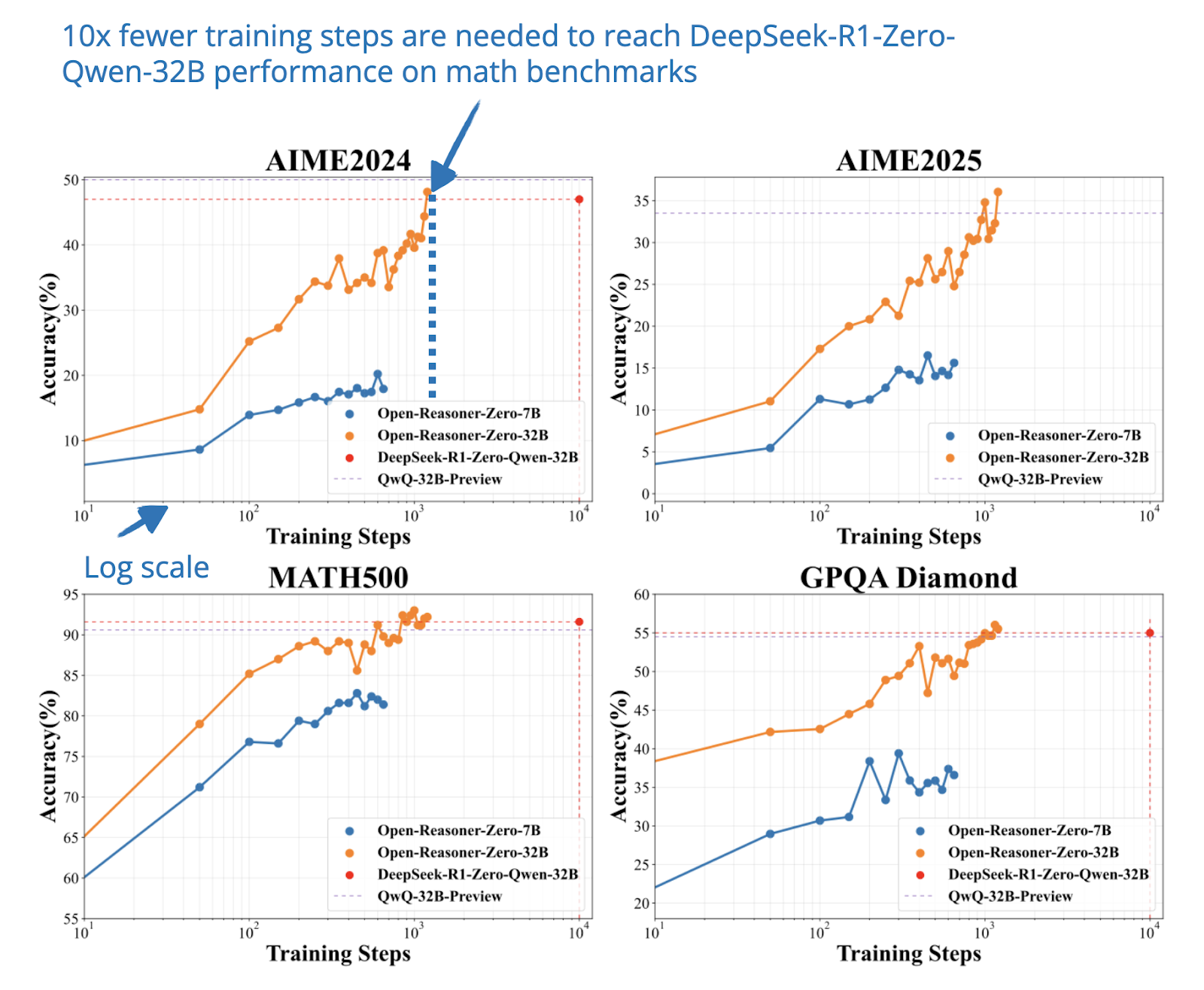

Using the same Qwen-32B base as DeepSeek-R1-Zero, their model outperforms it on multiple reasoning benchmarks while requiring only 1/10 the training steps.

[13] Rethinking Reflection in Pre-Training

📄 5 Apr, Rethinking Reflection in Pre-Training, https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.04022

Based on the interesting insights from the DeepSeek-R1 paper, namely applying pure RL to a base model, we think that reasoning abilities in LLMs emerge from RL. This paper provides a bit of a plot twist, saying that self-correction already appears earlier during pre-training.

Concretely, by introducing deliberately flawed chains-of-thought into tasks, the authors measure whether models can identify and correct these errors. They find that both explicit and implicit forms of reflection emerge steadily throughout pre-training. This happens across many domains and model sizes. Even relatively early checkpoints show signs of self-correction, and the ability becomes stronger as pre-training compute increases.

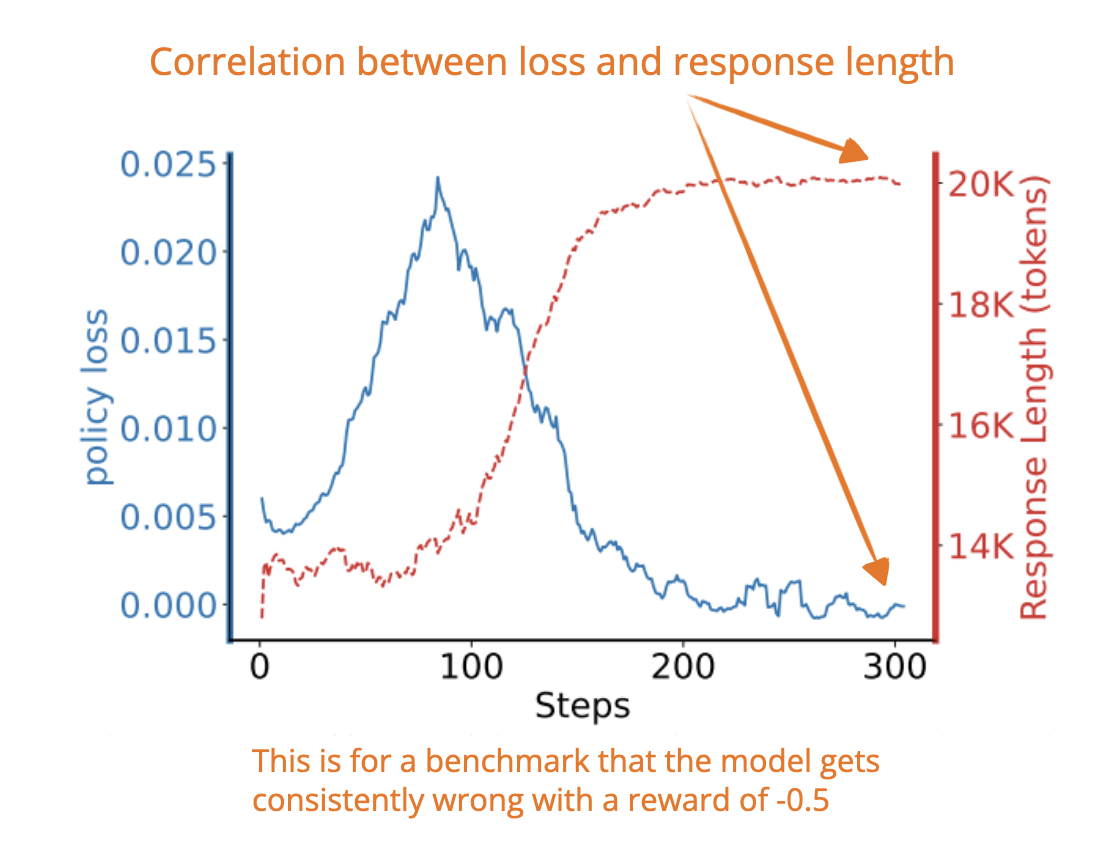

[14] Concise Reasoning via Reinforcement Learning

📄 7 Apr, Concise Reasoning via Reinforcement Learning, https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.05185

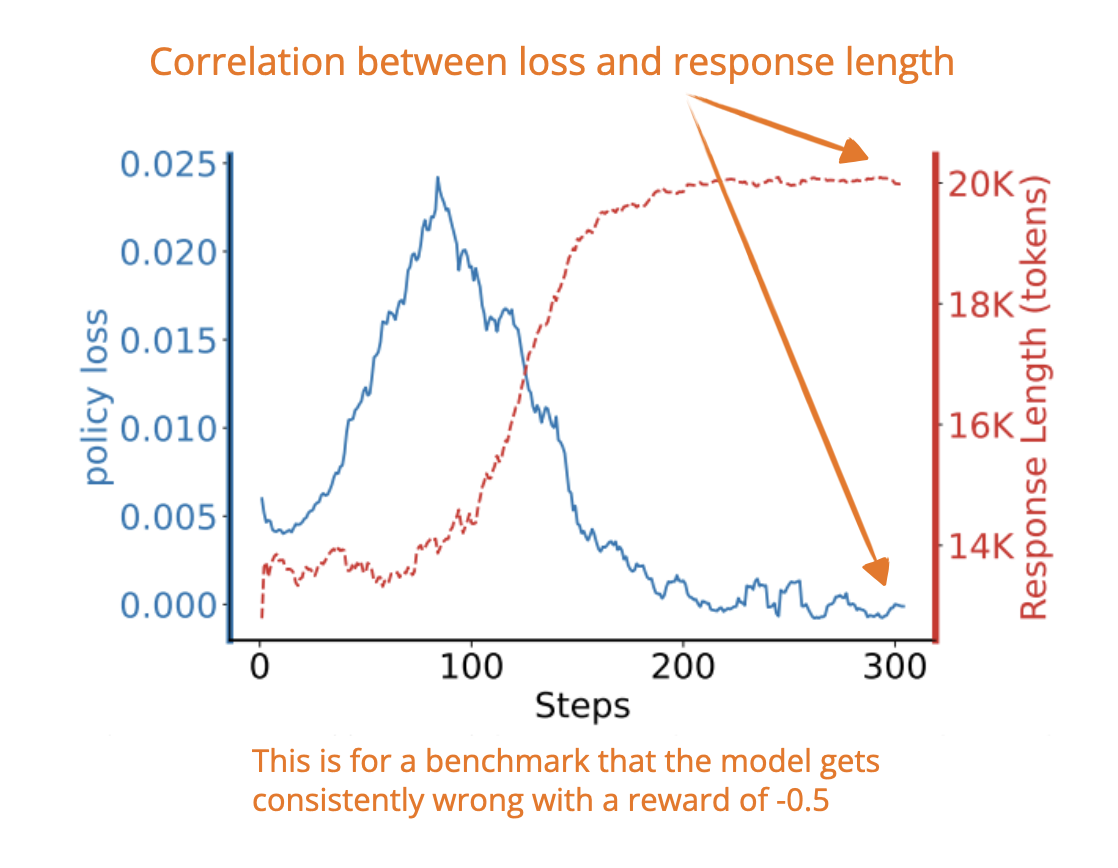

As we all know by now, reasoning models often generate longer responses, which raises compute costs. Now, this new paper shows that this behavior comes from the RL training process, not from an actual need for long answers for better accuracy. The RL loss tends to favor longer responses when the model gets negative rewards, which I think explains the “aha” moments and longer chains of thought that arise from pure RL training.

I.e., if the model gets a negative reward (i.e., the answer is wrong), the math behind PPO causes the average per-token loss becomes smaller when the response is longer. So, the model is indirectly encouraged to make its responses longer. This is true even if those extra tokens don’t actually help solve the problem.

What does the response length have to do with the loss? When the reward is negative, longer responses can dilute the penalty per individual token, which results in lower (i.e., better) loss values (even though the model is still getting the answer wrong).

So the model “learns” that longer responses reduce the punishment, even though they are not helping correctness.

However, it’s important to emphasize that this analysis was done for PPO:

Of note, our current analysis is not applicable to GRPO, and a precise analysis of such methods is left for future work.

In addition, the researchers show that a second round of RL (using just a few problems that are sometimes solvable) can shorten responses while preserving or even improving accuracy. This has big implications for deployment efficiency.

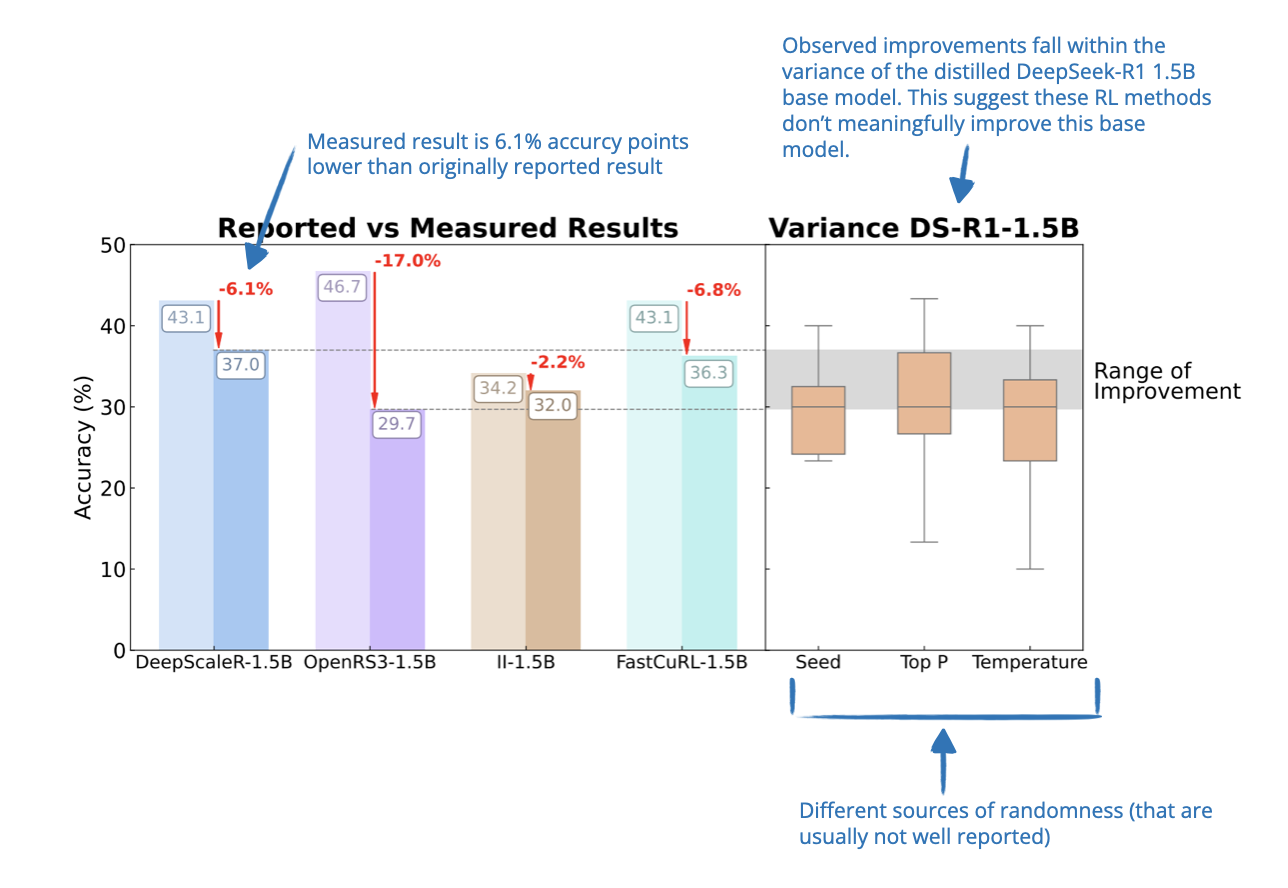

[15] A Sober Look at Progress in Language Model Reasoning

📄 9 Apr, A Sober Look at Progress in Language Model Reasoning: Pitfalls and Paths to Reproducibility, https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.07086

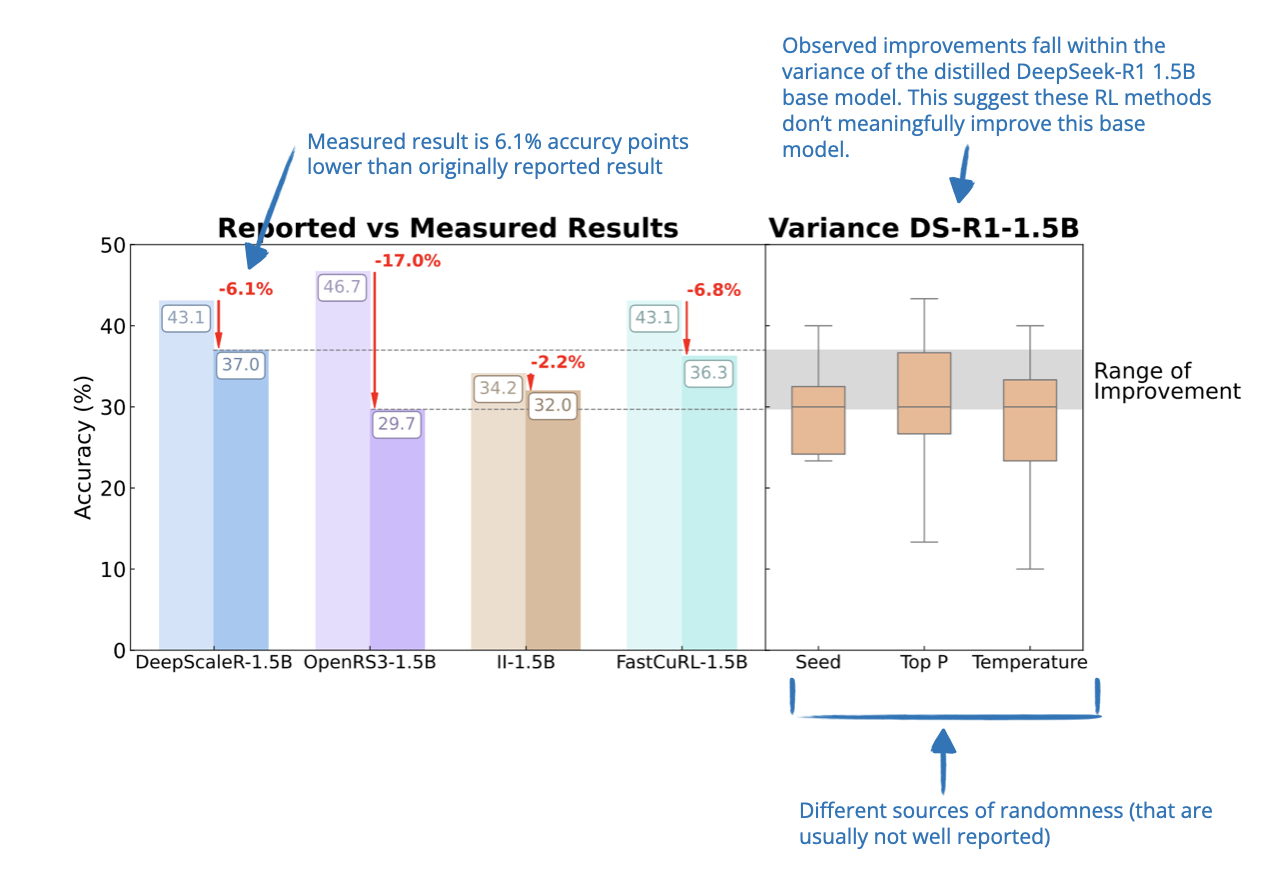

This paper takes a closer look at recent claims that RL can improve distilled language models, like those based on DeepSeek-R1.

For instance, I previously discussed the “20 Mar, Reinforcement Learning for Reasoning in Small LLMs: What Works and What Doesn’t” paper that found RL is effective for distilled models.

And also the DeepSeek-R1 paper mentioned

Additionally, we found that applying RL to these distilled models yields significant further gains. We believe this warrants further exploration and therefore present only the results of the simple SFT-distilled models here.

So, while earlier papers reported large performance boosts from RL, this work finds that many of those improvements might just be noise. The authors show that results on small benchmarks like AIME24 are highly unstable: just changing a random seed can shift scores by several percentage points.

When RL models are evaluated under more controlled and standardized setups, the gains turn out to be much smaller than originally reported, and often not statistically significant. However, some models trained with RL do show modest improvements, but these are usually weaker than what supervised fine-tuning achieves, and they often don’t generalize well to new benchmarks.

So, while RL might help in some cases to improve smaller distilled models, this paper argues that its benefits have been overstated and better evaluation standards are needed to understand what’s actually working.

If you read the book and have a few minutes to spare, I'd really appreciate a brief review. It helps us authors a lot!

Your support means a great deal! Thank you!