New LLM Pre-training and Post-training Paradigms

-- A Look at How Moderns LLMs Are Trained

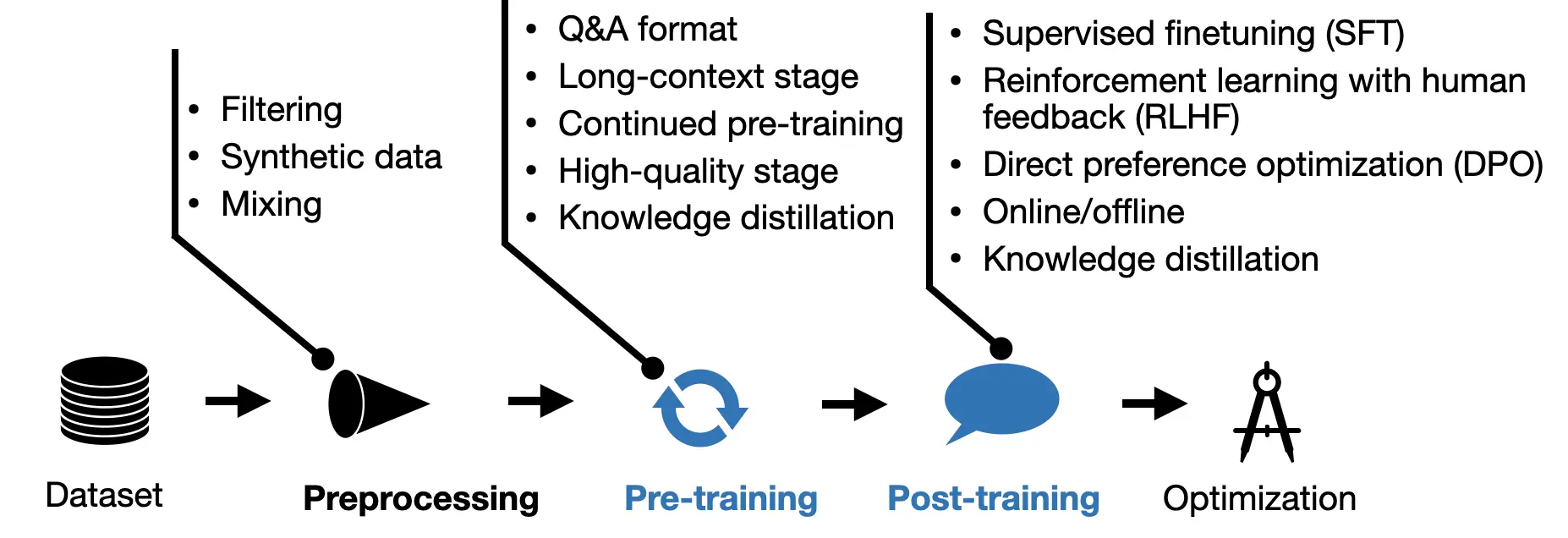

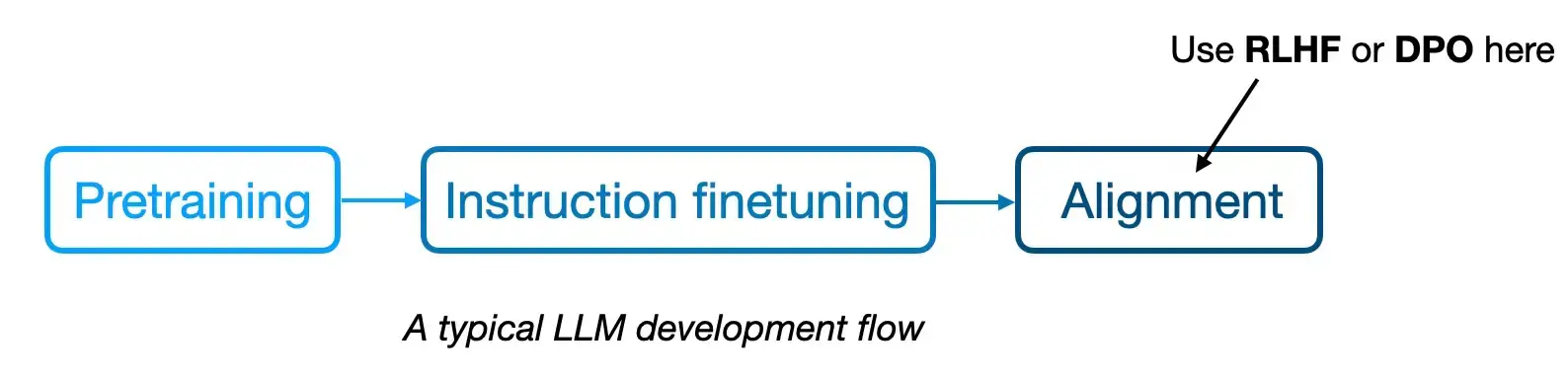

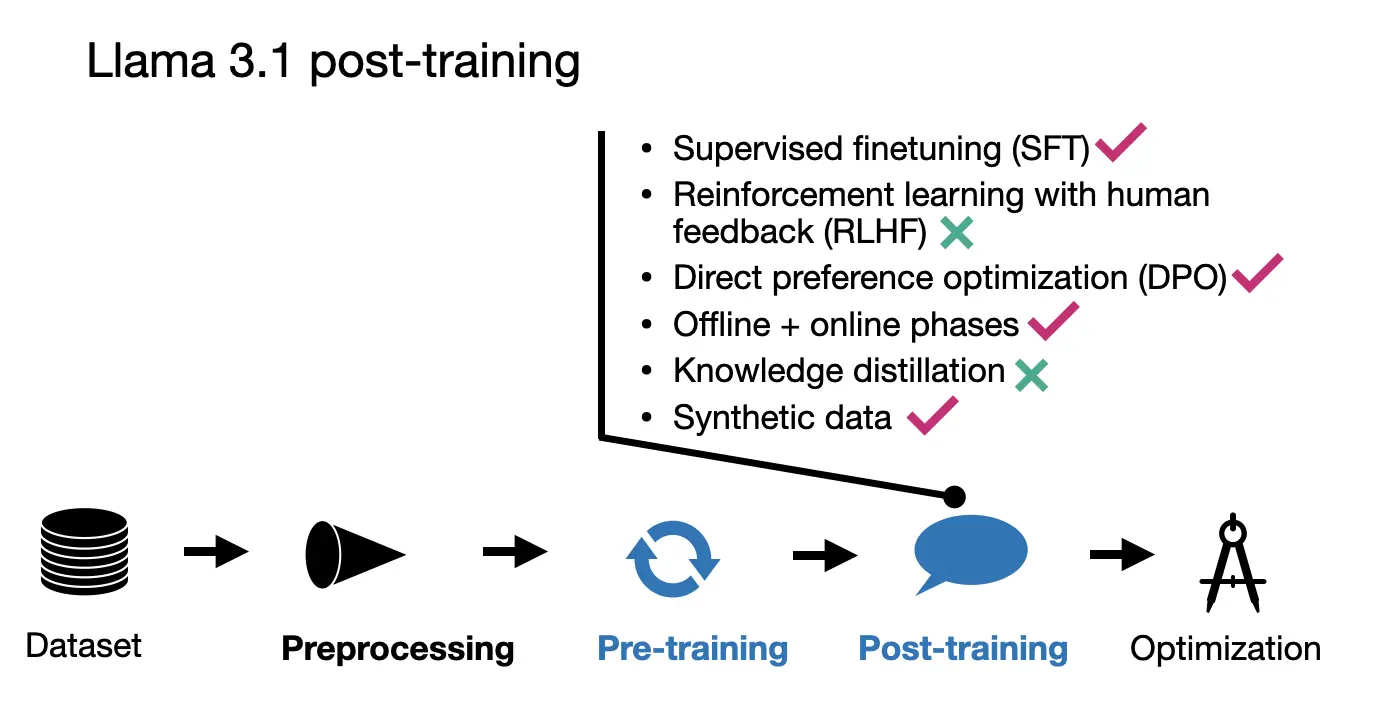

The development of large language models (LLMs) has come a long way, from the early GPT models to the sophisticated open-weight LLMs we have today. Initially, the LLM training process focused solely on pre-training, but it has since expanded to include both pre-training and post-training. Post-training typically encompasses supervised instruction fine-tuning and alignment, which was popularized by ChatGPT.

Training methodologies have evolved since ChatGPT was first released. In this article, I review the latest advancements in both pre-training and post-training methodologies, particularly those made in recent months.

There are hundreds of LLM papers each month proposing new techniques and approaches. However, one of the best ways to see what actually works well in practice is to look at the pre-training and post-training pipelines of the most recent state-of-the-art models. Luckily, four major new LLMs have been released in the last months, accompanied by relatively detailed technical reports.

In this article, I focus on the pre-training and post-training pipelines of the following models:

- Alibaba’s Qwen 2

- Apple Intelligence Foundation Language Models

- Google’s Gemma 2

- Meta AI’s Llama 3.1

These models are presented in order based on the publication dates of their respective technical papers on arXiv.org, which also happens to align with their alphabetical order.

This article is a passion project that I created in my free time and over the weekends. If you find it valuable and would like to support my work, please consider purchasing a copy of my books and recommending them to your colleagues. Your review on Amazon would also be greatly appreciated!

- Build a Large Language Model (from Scratch) is a highly focused book dedicated to coding LLMs from the ground up in PyTorch, covering everything from pre-training to post-training—arguably the best way to truly understand LLMs.

- Machine Learning Q and AI is a great book for those who are already familiar with the basics; it dives into intermediate and advanced concepts covering deep neural networks, vision transformers, multi-GPU training paradigms, LLMs, and many more.

- Machine Learning with PyTorch and Scikit-Learn is a comprehensive guide to machine learning, deep learning, and AI, offering a well-balanced mix of theory and practical code. It’s the ideal starting point for anyone new to the field.

1. Alibaba’s Qwen 2

Let’s begin with Qwen 2, a really strong LLM model family that is competitive with other major LLMs. However, for some reason, it’s less popular than the open-weight models from Meta AI, Microsoft, and Google.

1.1 Qwen 2 Overview

Before looking at the pre-training and post-training methods discussed in the Qwen 2 Technical Report, let’s briefly summarize some core specifications.

Qwen 2 models come in 5 flavors. There are 4 regular (dense) LLMs with sizes 0.5 billion, 1.5 billion, 7 billion, and 72 billion parameters. In addition, there is a Mixture-of-Experts model with 57 billion parameters, where 14 billion parameters are activated at the same time. (Since architecture details are not the focus this time, I won’t go too much into the Mixture-of-Experts model; however, in a nutshell, this is similar to Mixtral by Mistral AI, except that it has more active experts. For a high-level overview, see the Mixtral Architecture section in my Model Merging, Mixtures of Experts, and Towards Smaller LLMs article.)

One of the stand-out features of Qwen 2 LLMs are their good multilingual capabilities in 30 languages. They also have a surprisingly large 151,642 token vocabulary (for reference, Llama 2 uses a 32k vocabulary, and Llama 3.1 uses a 128k token vocabulary); as a rule of thumb, increasing the vocab size by 2x reduces the number of input tokens by 2x so we can fit more text into the same input. Also it especially helps with multilingual data and coding to cover words outside the standard English vocabulary.

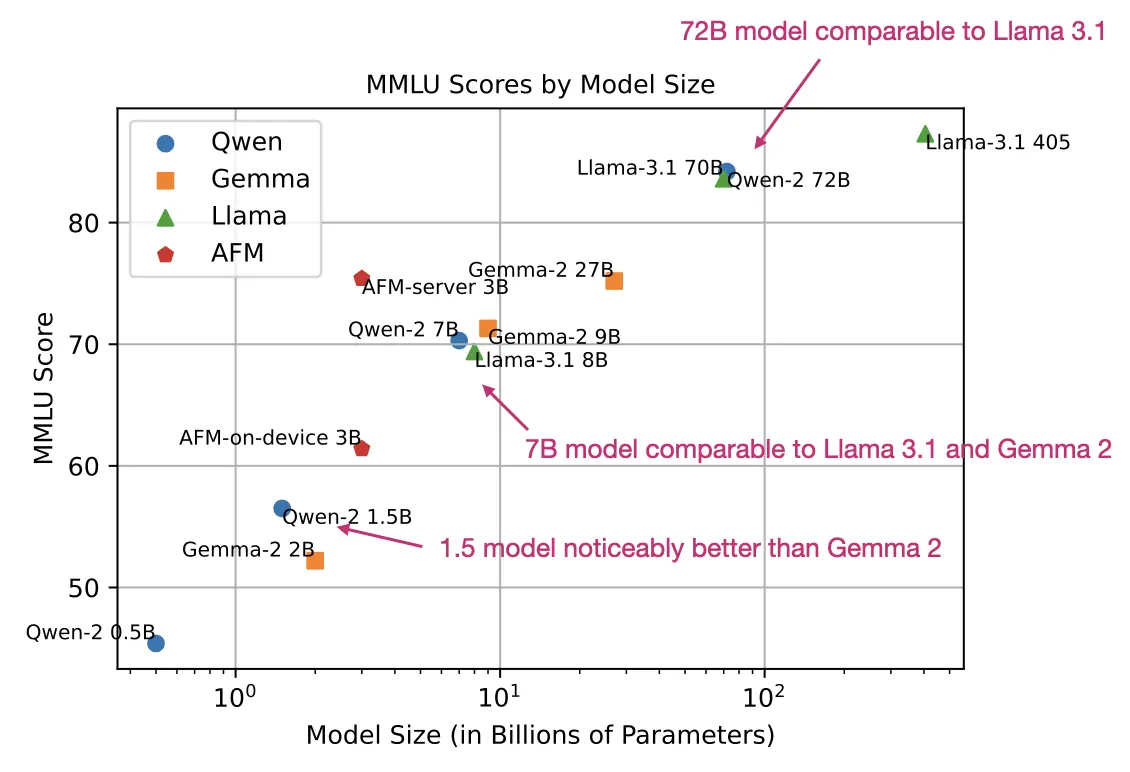

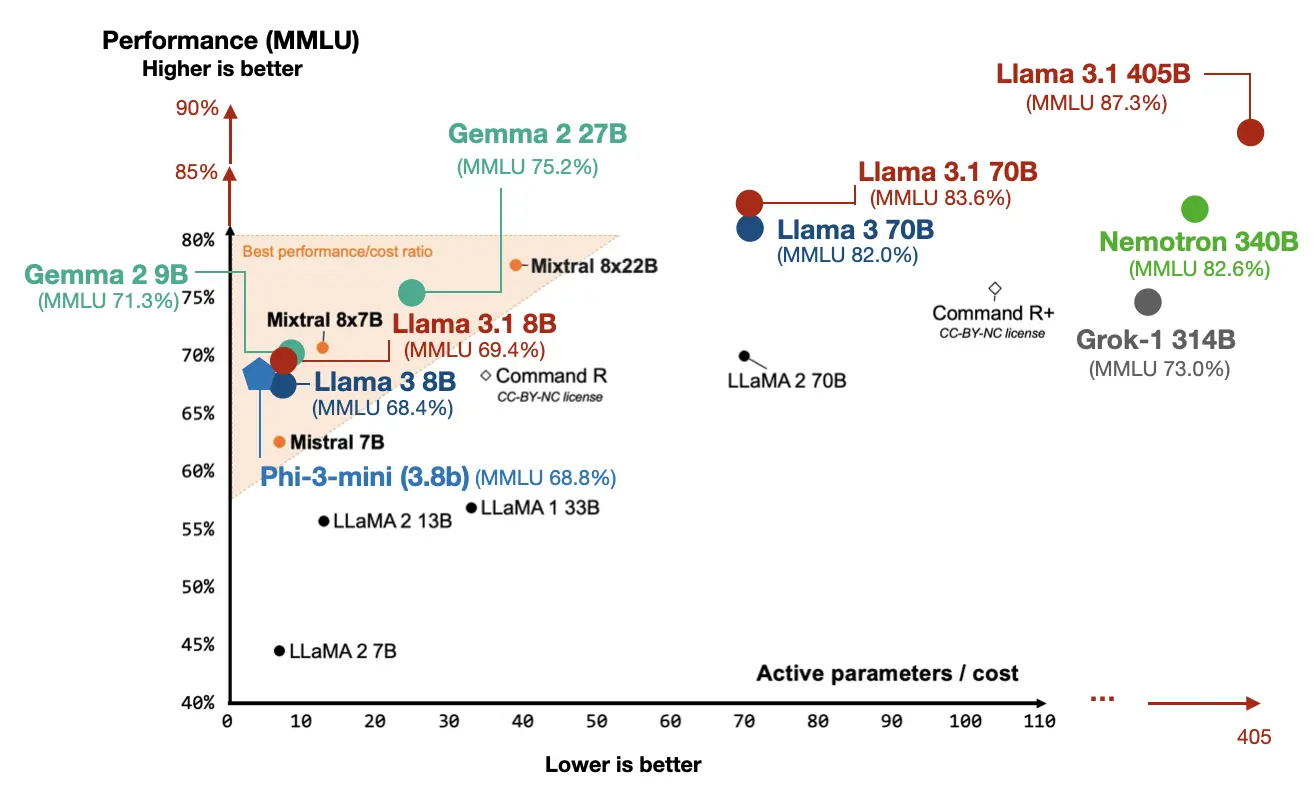

Below is a brief MMLU benchmark comparison with other LLMs covered later. (Note that MMLU is a multiple-choice benchmark and thus has its limitations; however, it still is one of the most popular methods for reporting LLM performance.)

(If you are new to MMLU, I briefly discussed it in my recent talk at minute 46:05.)

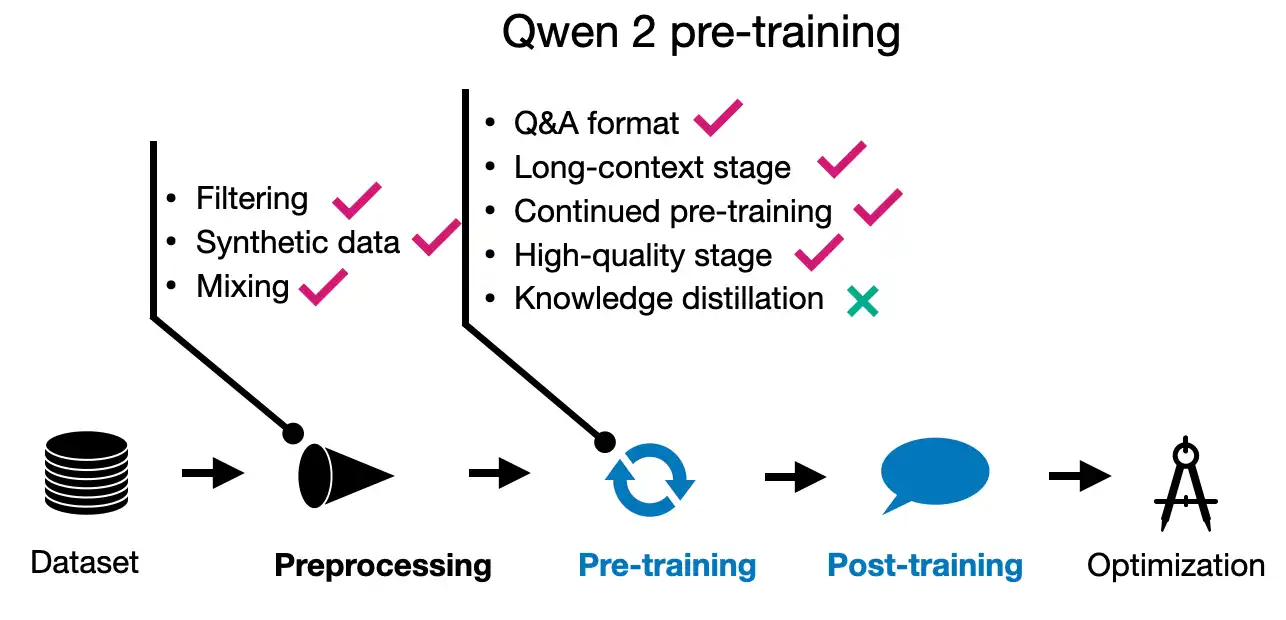

1.2 Qwen 2 Pre-training

The Qwen 2 team trained the 1.5 billion, 7 billion, and 72 billion parameter models on 7 trillion training tokens, which is a reasonable size. For comparison, Llama 2 models were trained on 2 trillion tokens, and Llama 3.1 models were trained on 15 trillion tokens.

Interestingly, the 0.5 billion parameter model was trained on 12 trillion tokens. However, the researchers did not train the other models on the larger 12 trillion token dataset because they did not observe any improvements during training, and the additional computational costs were not justified.

One of the focus areas has been improving the data filtering pipeline to remove low-quality data and enhancing data mixing to increase data diversity— a theme we will revisit when examining other models later.

Interestingly, they also used Qwen models (although they didn’t specify details, I assume they mean previous generation Qwen models) to synthesize additional pre-training data. And the pre-training involved “multi-task instruction data… to enhance in-context learning and instruction-following abilities.”

Furthermore, they performed training in two stages: regular pre-training followed by long-context training. The latter increased the context length from 4,096 to 32,768 tokens at the end phase of pre-training using “high-quality, lengthy data.”

(Unfortunately, another theme of the technical reports is that details about the dataset are scarce, so if my write-up does not appear very detailed, it’s due to the lack of publicly available information.)

1.3 Qwen 2 Post-training

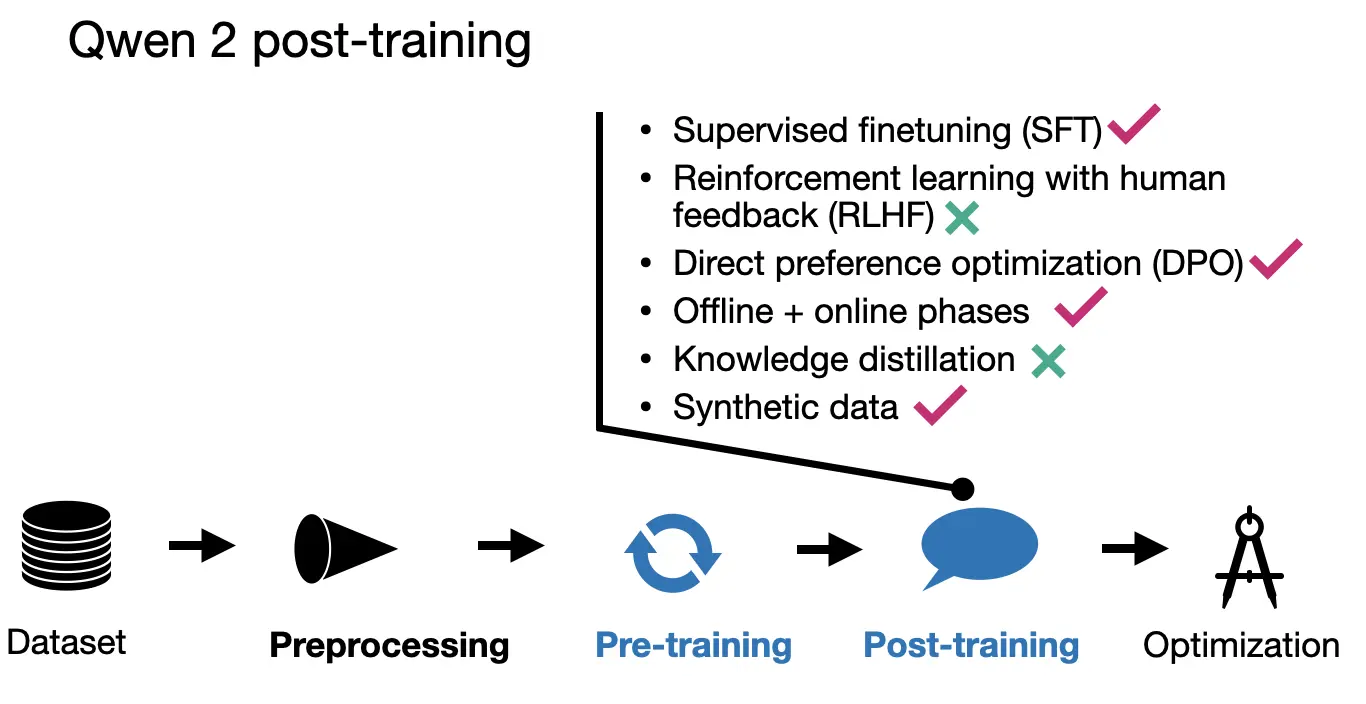

The Qwen 2 team employed the popular two-phase post-training methodology, starting with supervised instruction fine-tuning (SFT), which was applied across 500,000 examples for 2 epochs. This phase aimed to refine the model’s response accuracy in predetermined scenarios.

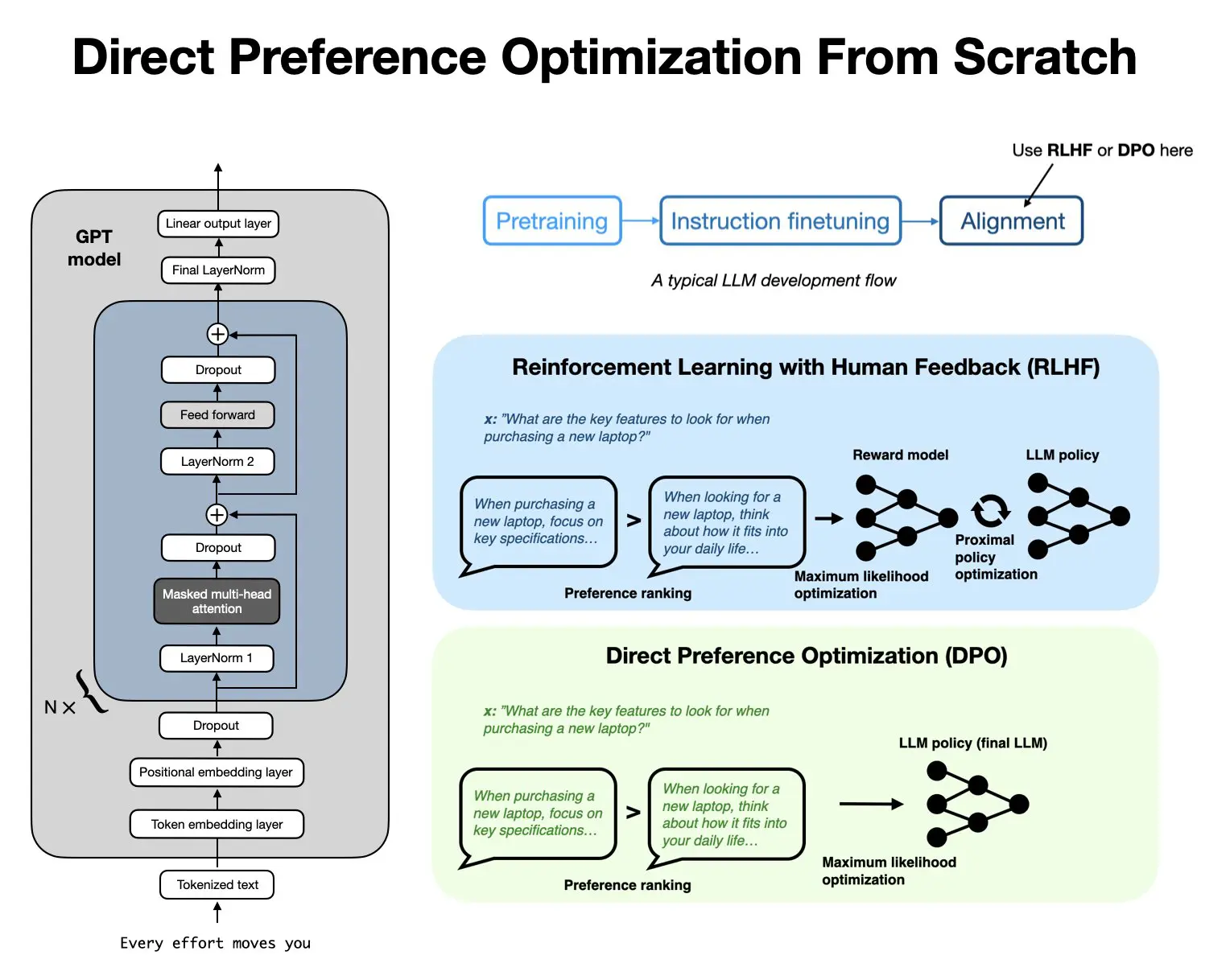

After SFT, they used direct preference optimization (DPO) to align the LLM with human preferences. (Interestingly referred to in their terminology as reinforcement learning from human feedback, RLHF.) As I discussed in my Tips for LLM Pretraining and Evaluating Reward Models article a few weeks ago, the SFT+DPO approach seems to be the most popular preference tuning strategy at the moment due to the ease of use compared to other methods, such as RLHF with PPO. (If you want to learn how DPO works, I recently implemented it from scratch here.)

The alignment phase itself was also done in 2 stages. First using DPO on an existing dataset (offline stage). Second, using a reward model to form the preference pair (online). Here, the model generates multiple responses during training, and a reward model selects the preferred response for the optimization step in “real-time” (that is, during training). This is also often referred to as “rejection sampling.”

For the construction of the dataset, they used existing corpora complemented by human labeling to determine target responses for SFT and identify preferred and rejected responses essential for DPO. The researchers also synthesized artificially annotated data.

Moreover, the team used LLMs to generate instruction-response pairs specifically tailored for “high-quality literary data,” to create high-quality Q&A pairs for training.

1.4 Conclusion

Qwen 2 is a relatively capable model, and similar to earlier generations of Qwen. When attending the NeurIPS LLM efficiency challenge in December 2023, I remember that most of the winning approaches involved a Qwen model.

Regarding the training pipeline of Qwen 2, what stands out is that synthetic data has been used for both pre-training and post-training. Also, the focus on dataset filtering (rather than collecting as much data as possible) is one of the notable trends in LLM training. Here, I would say, more is better, but only if it meets certain quality standards.

Aligning LLMs with Direct Preference Optimization from Scratch

Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) has become one of the go-to methods to align LLMs more closely with user preferences, and it’s something you will read a lot in this article. If you want to learn how it works, I coded it from scratch here: Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) for LLM Alignment (From Scratch).

2. Apple’s Apple Intelligence Foundation Language Models (AFM)

I was really delighted to see another technical paper by Apple on arXiv.org that outlines their model training. An unexpected but definitely positive surprise!

2.1 AFM Overview

In the Apple Intelligence Foundation Language Models paper, available at, the research team outlines the development of two primary models designed for use in the “Apple Intelligence” context on Apple devices. For brevity, these models will be abbreviated as AFM for “Apple Foundation Models” throughout this section.

Specifically, the paper describes two versions of the AFM: a 3-billion-parameter on-device model intended for deployment on phones, tablets, or laptops, and a more capable server model of unspecified size.

These models are developed for chat, math, and coding tasks, although the paper does not discuss any of the coding-specific training and capabilities.

Like the Qwen 2, the AFMs are dense LLMs and do not utilize a mixture-of-experts approach.

2.2 AFM Pre-training

I’d like to extend two big kudos to the researchers. First, besides using publicly available data and data licensed by publishers, they respected the robots.txt files on websites and refrained from crawling these. Second, they also mentioned that they performed decontamination with benchmark data.

To reinforce one of the takeaways of the Qwen 2 paper, the researchers mentioned that quality was much more important than quantity. (With a vocabulary size of 49k tokens for the device model and 100k tokens for the server model, the vocabulary sizes were noticeably smaller than those of the Qwen 2 models, which used 150k token vocabulary.)

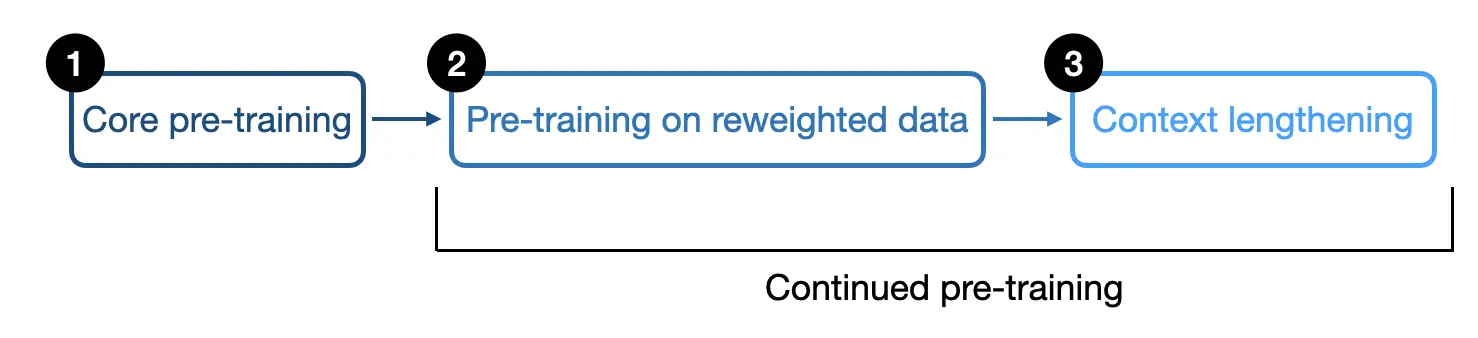

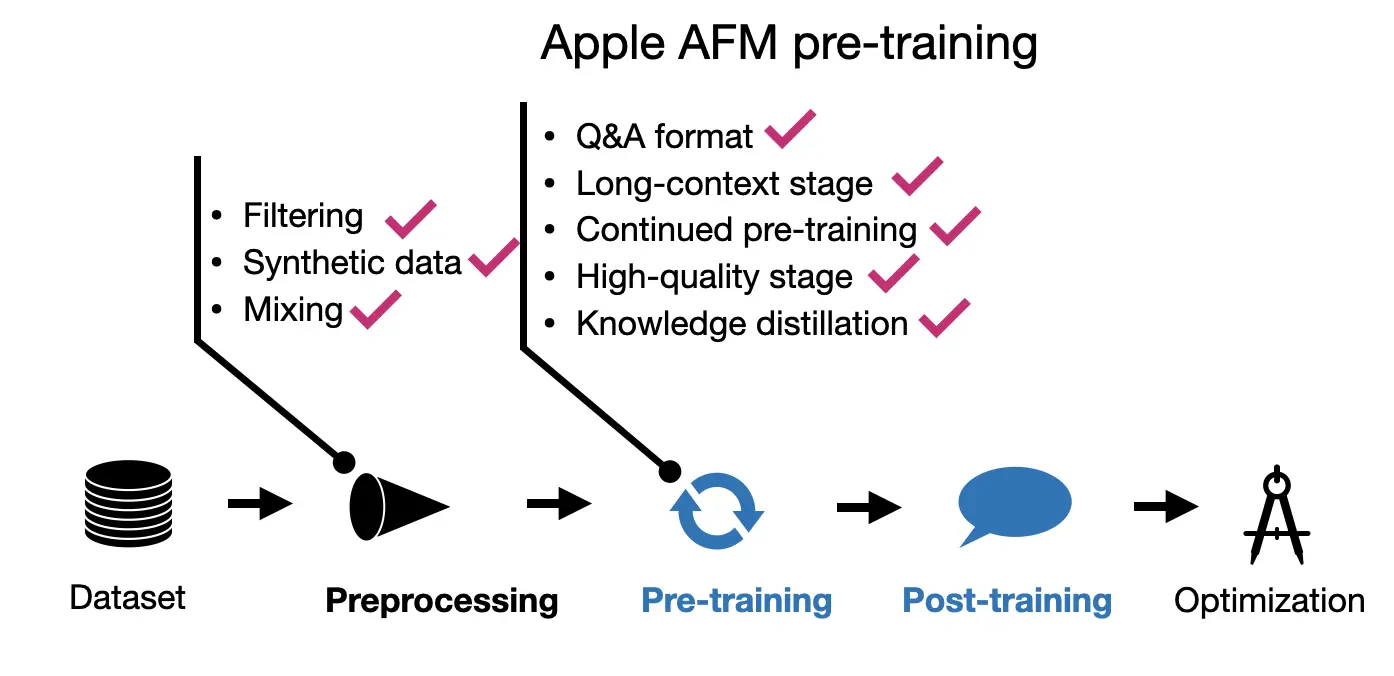

Interestingly, the pre-training was not done in 2 but 3 stages!

- Core (regular) pre-training

- Continued pre-training where web-crawl (lower-quality) data was down-weighted; math and code was up-weighted

- Context-lengthening with longer sequence data and synthetic data

Let’s take a look at these 3 steps in a bit more detail.

2.2.1 Pre-training I: Core Pre-training

Core pre-training describes the first pre-training stage in Apple’s pre-training pipeline. This is akin to regular pre-training, where the AFM-server model was trained on 6.3 trillion tokens, a batch size of 4096 batch size and a 4096-token sequence length. This is very similar to Qwen 2 models, which were trained in 7 trillion tokens.

However, it gets more interesting for the AFM-on-device model, which is distilled and pruned from a larger 6.4-billion-parameter model (trained from scratch like the AFM-server model described in the previous paragraph.

There’s not much detail on the distillation process besides “a distillation loss is used by replacing the target labels with a convex combination of the true labels and the teacher model’s top-1 predictions (with 0.9 weight assigned to the teacher labels).”

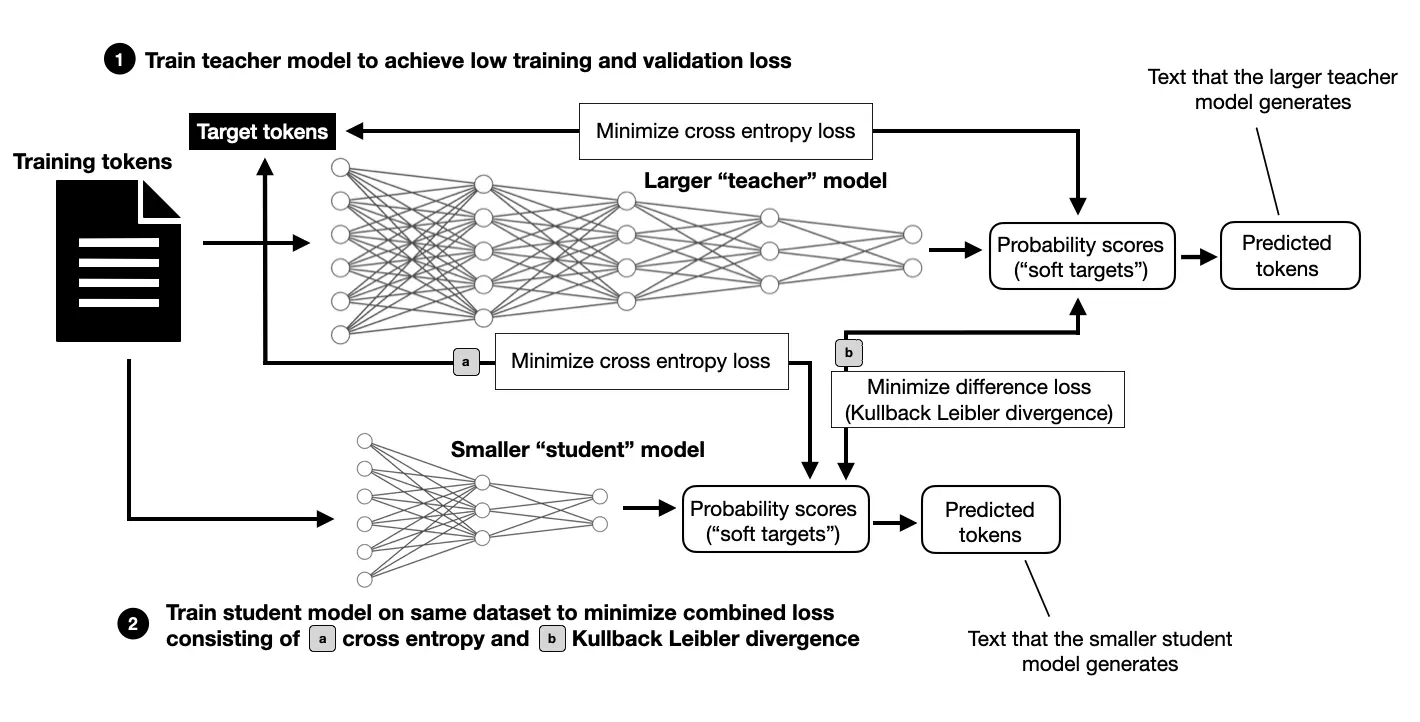

I feel that knowledge distillation is becoming increasingly prevalent and useful for LLM pre-training (Gemma-2 uses it, too). I plan to cover it in more detail one day. For now, here’s a brief overview of how this process would work on a high level.

Knowledge distillation, as illustrated above, still involves training on the original dataset. However, in addition to the training tokens in the dataset, the model to be trained (referred to as the student) receives information from the larger (teacher) model, which provides a richer signal compared to training without knowledge distillation. The downside is that you must: 1) train the larger teacher model first, and 2) compute predictions on all training tokens using the larger teacher model. These predictions can be computed ahead of time (which requires substantial storage space) or during training (which may slow down the training process).

2.2.2 Pre-training II: Continued Pre-training

The continued pre-training stage includes a small context lengthening step from 4,096 to 8,192 tokens on a dataset consisting of 1 trillion tokens (the core pre-training set was five times larger). The primary focus, however, is on training with a high-quality data mix, with an emphasis on math and code.

Interestingly, the researchers found that the distillation loss was not beneficial in this context.

2.2.3 Pre-training III: Context Lengthening

The third pre-training stage involves only 100 billion tokens (10% of the tokens used in the second stage) but represents a more significant context lengthening to 32,768 tokens. To achieve this, the researchers augmented the dataset with synthetic long-context Q&A data.

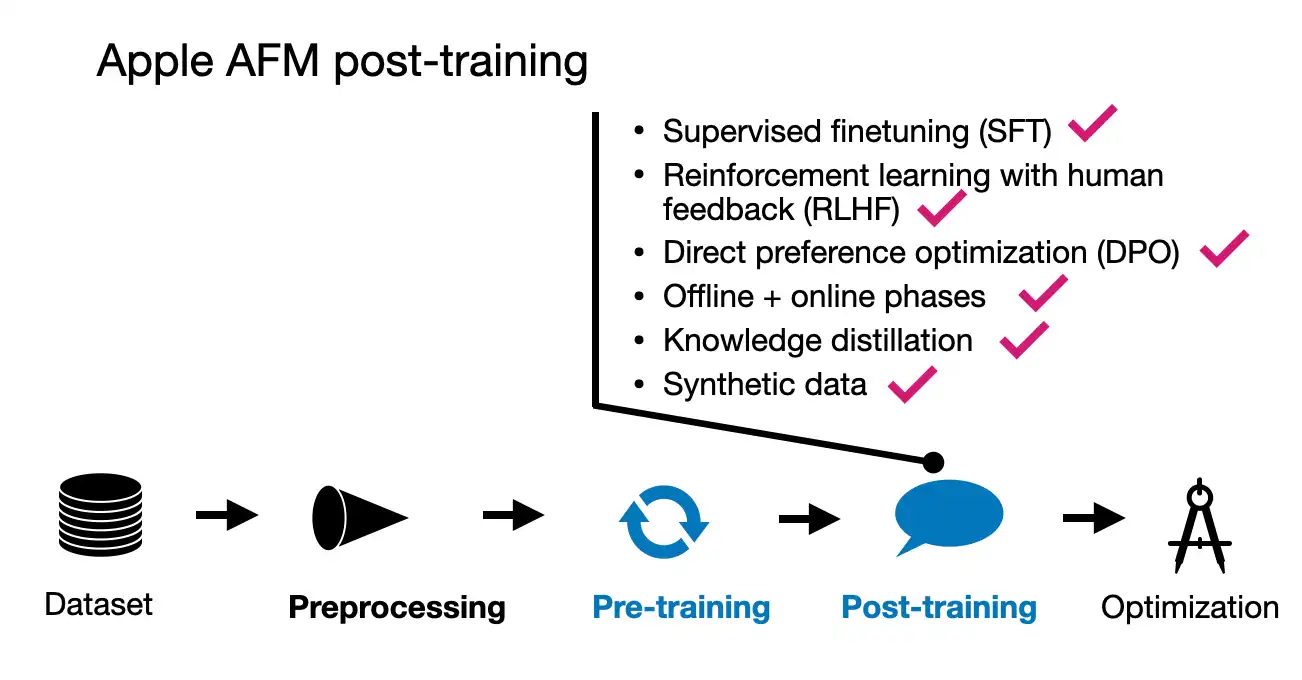

2.3 AFM Post-training

Apple appears to have taken a similarly comprehensive approach to their post-training process as they did with pre-training. They leveraged both human-annotated and synthetic data, emphasizing that data quality was prioritized over quantity. Interestingly, they did not rely on predetermined data ratios; instead, they fine-tuned the data mixture through multiple experiments to achieve the optimal balance.

The post-training phase involved a two-step process: supervised instruction fine-tuning followed by several rounds of reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF).

A particularly noteworthy aspect of this process is Apple’s introduction of two new algorithms for the RLHF stage:

- Rejection Sampling Fine-tuning with Teacher Committee (iTeC)

- RLHF with Mirror Descent Policy Optimization

Given the length of this article, I won’t go into the technical details of these methods, but here’s a brief overview:

The iTeC algorithm combines rejection sampling with multiple preference tuning techniques—specifically, SFT, DPO, IPO, and online RL. Rather than relying on a single algorithm, Apple trained models using each approach independently. These models then generated responses, which were evaluated by humans who provided preference labels. This preference data was used to iteratively train a reward model in an RLHF framework. During the rejection sampling phase, a committee of models generated multiple responses, with the reward model selecting the best one.

This committee-based approach is quite complex but should be relatively feasible, particularly given the relatively small size of the models involved (around 3 billion parameters). Implementing such a committee with much larger models, like the 70B or 405B parameter models in Llama 3.1, would definitely be more challenging.

As for the second algorithm, RLHF with Mirror Descent, it was chosen because it proved more effective than the commonly used PPO (Proximal Policy Optimization).

2.4 Conclusion

Apple’s approach to pre-training and post-training is relatively comprehensive, likely because the stakes are very high (the model is deployed on millions, if not billions, of devices). However, given the small nature of these models, a vast array of techniques also becomes feasible, since a 3B model is less than half the size of the smallest Llama 3.1 model.

One of the highlights is that it’s not a simple choice between RLHF and DPO; instead, they used multiple preference-tuning algorithms in the form of a committee.

It’s also interesting that they explicitly used Q&A data as part of the pre-training—something I discussed in my previous article, Instruction Pretraining LLMs.

All in all, it’s a refreshing and delightful technical report.

3. Google’s Gemma 2

Google’s Gemma models were recently described in Gemma 2: Improving Open Language Models at a Practical Size.

I’ll provide an overview of some of key facts in the following overview section before discussing the pre-training and post-training processes.

3.1 Gemma 2 Overview

The Gemma 2 models are available in three sizes: 2 billion, 9 billion, and 27 billion parameters. The primary focus is on exploring techniques that do not necessarily require increasing the size of training datasets but rather on developing relatively small and efficient LLMs.

Notably, Gemma 2 features a substantial vocabulary size of 256k tokens. For comparison, Llama 2 uses a 32k token vocabulary, and Llama 3 has a 128k token vocabulary.

Additionally, Gemma 2 employs sliding window attention, similar to Mistral’s early models, likely to reduce memory costs. For more details on the Gemma 2 architecture, please refer to the Gemma 2 section in my previous article.

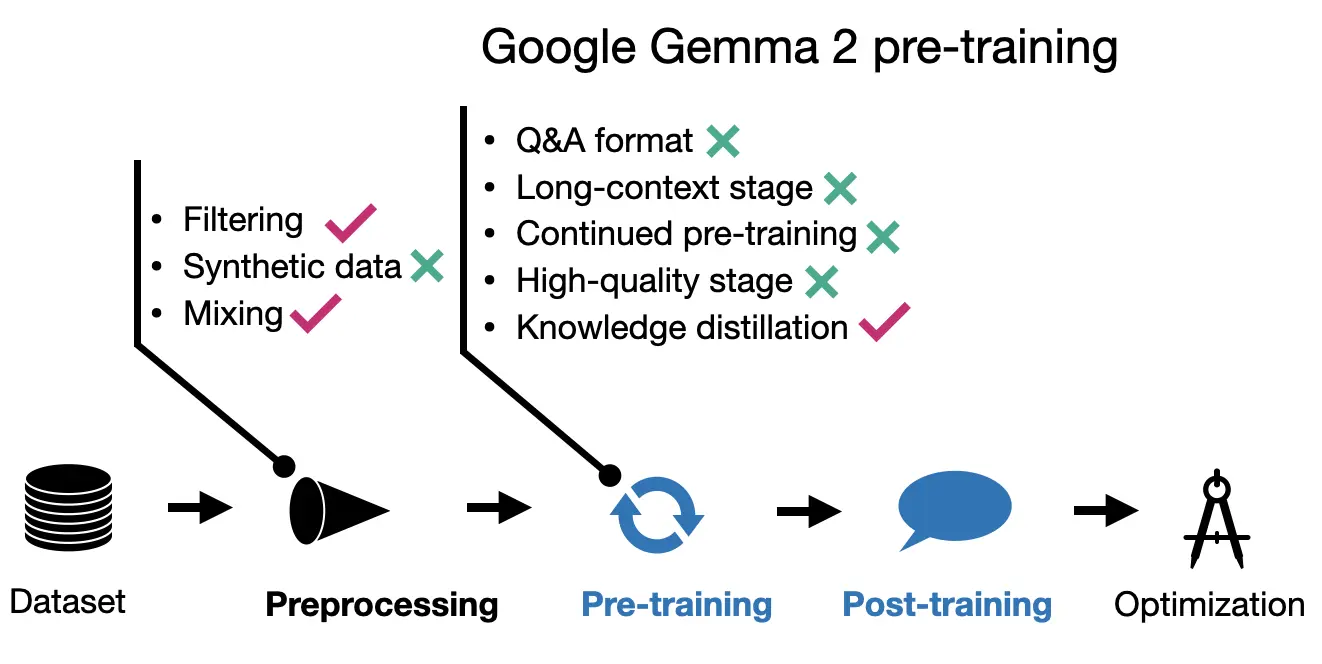

3.2 Gemma 2 Pre-training

The Gemma researchers argue that even small models are often undertrained. However, rather than simply increasing the size of the training dataset, they focus on maintaining quality and achieve improvements through alternative methods, such as knowledge distillation, similar to Apple’s approach.

While the 27B Gemma 2 model was trained from scratch, the smaller models were trained using knowledge distillation similar to Apple’s approach explained previously.

The 27B model was trained on 13 trillion tokens, the 9B model on 8 trillion tokens, and the 2B model on 2 trillion tokens. Additionally, similar to Apple’s approach, the Gemma team optimized the data mixture to improve performance.

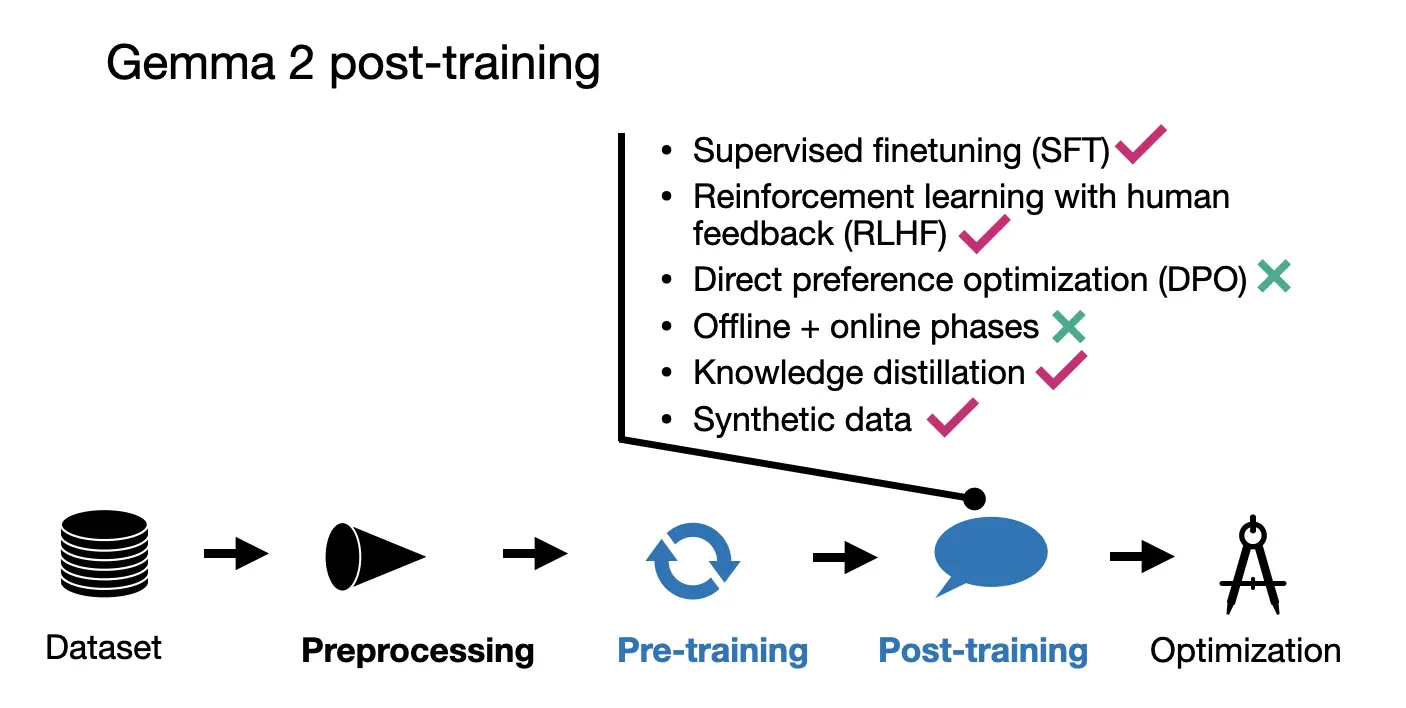

3.3 Gemma 2 Post-training

The post-training process for the Gemma models involved the typical supervised fine-tuning (SFT) and reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF) steps.

The instruction data involved using English-only prompt pairs, which were a mix of human-generated and synthetic-generated content. Specifically, and interestingly, the responses were primarily generated by teacher models, and knowledge distillation was also applied during the SFT phase.

An interesting aspect of their RLHF approach, following SFT, is that the reward model used for RLHF is ten times larger than the policy (target) model.

The RLHF algorithm employed by Gemma is fairly standard, but with a unique twist: they average the policy models through a method called WARP, a successor to WARM (weight-averaged reward models). I previously discussed this method in detail in my article “Model Merging, Mixtures of Experts, and Towards Smaller LLMs”.

3.4 Conclusion

The Gemma team seems to really double down on knowledge distillation, which they use during both pre-training and post-training similar to Apple. Interestingly, they didn’t use a multi-stage pre-training approach though, or at least, they didn’t detail it in their paper.

4. Meta AI’s Llama 3.1

New releases of Meta’s Llama LLMs are always a big thing. This time, the release was accompanied by a 92-page technical report: The Llama 3 Herd of Models. Last but not least, in this section, we will look at the fourth big model paper released last month.

4.1 Llama 3.1 Overview

Along with releasing a huge 405 billion parameter model, Meta updated their previous 8 billion and 70 billion parameter models, giving them a slight MMLU performance boost.

While Llama 3 uses group query attention like other recent LLMs, surprisingly, Meta AI said no to sliding window attention and Mixture-of-Experts approaches. In other words, the Llama 3.1 looks very traditional, and the focus was clearly on the pre-training and post-training rather than architecture innovations.

Similar to previous Llama releases, the weights are openly available. Moreover, Meta said that they updated the Llama 3 license so that it’s now finally possible (allowed) to use Llama 3 for synthetic data generation or knowledge distillation to improve other models.

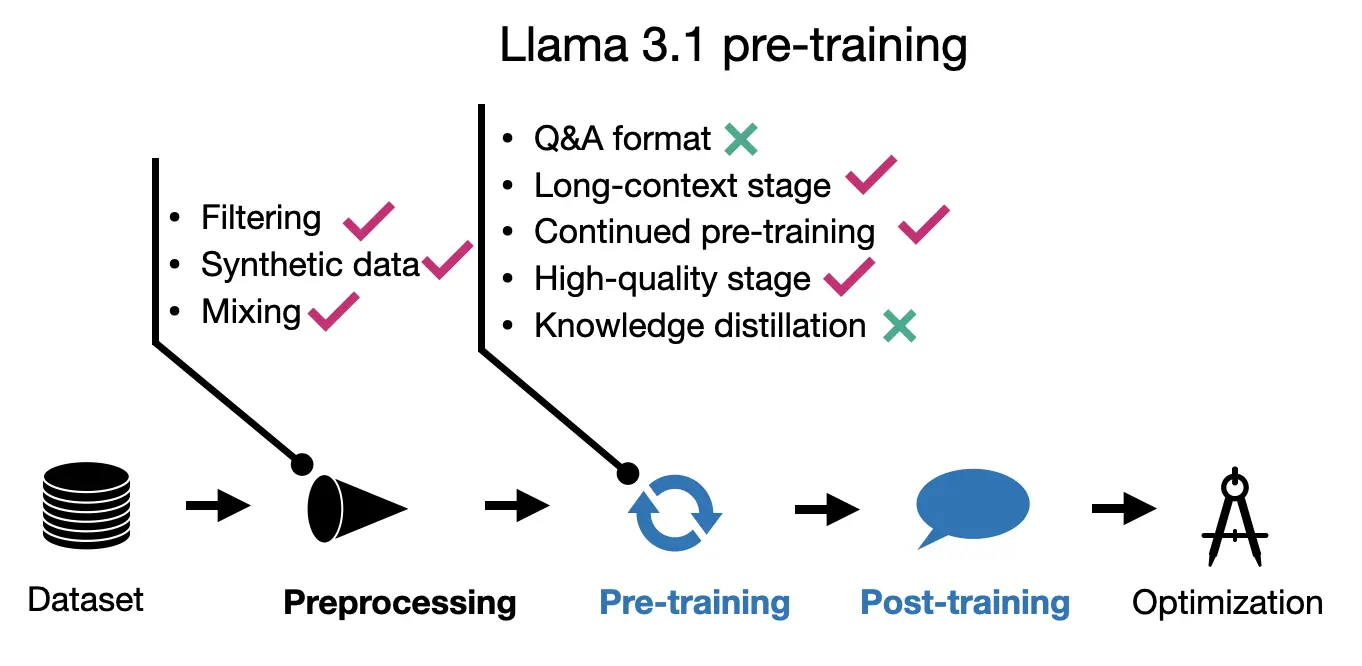

4.2 Llama 3.1 Pre-training

Llama 3 was trained on a massive 15.6 trillion tokens dataset, which is a substantial increase from Llama 2’s 1.8 trillion tokens. The researchers say that it supports at least eight languages, (whereas Qwen 2 is capable of handling 20).

An interesting aspect of Llama 3 is its vocabulary size of 128,000, which was developed using OpenAI’s tiktoken tokenizer. (For those interested in tokenizer performance, I did a simple benchmark comparison here.)

In terms of pre-training data quality control, Llama 3 employs heuristic-based filtering alongside model-based quality filtering, utilizing fast classifiers like Meta AI’s fastText and RoBERTa-based classifiers. These classifiers also help in determining the context categories for the data mix used during training.

The pre-training for Llama 3 is divided into three stages. The first stage involves standard initial pre-training using the 15.6 trillion tokens with an 8k context window. The second stage continues with the pre-training but extends the context length to 128k. The final stage involves annealing, which further enhances the model’s performance. Let’s look into these stages in more detail below.

4.2.1 Pre-training I: Standard (Initial) Pre-training

In their training setup, they began with batches consisting of 4 million tokens, each with a sequence length of 4096. This implies a batch size of approximately 1024 tokens, assuming that the 4 million figure is rounded to the nearest digit. After processing the first 252 million tokens, they doubled the sequence length to 8192. Further into the training process, after 2.87 trillion tokens, they doubled the batch size again.

Additionally, the researchers did not keep the data mix constant throughout the training. Instead, they adjusted the mix of data being used during the training process to optimize model learning and performance. This dynamic approach to data handling likely helped in improving the model’s ability to generalize across different types of data.

4.2.2 Pre-training II: Continued Pre-training for Context Lengthening

Compared to other models that increased their context window in a single step, the Llama 3.1 context lengthening was a more gradual approach: Here, the researchers increased the context length through six distinct stages from 8,000 to 128,000 tokens. This stepwise increment likelely allowed the model to adapt more smoothly to larger contexts.

The training set utilized for this process was involved 800 billion tokens, about 5% of the total dataset size.

4.2.3 Pre-training III: Annealing on High-quality Data

For the third pre-training stage, the researchers trained the model on a small but high-quality mix, which they found helps improve the performance on benchmark datasets. For example, annealing on the GSM8K and MATH training sets provided a significant boost on the respective GSM8K and MATH validation sets.

In section 3.1.3 of the paper, the researchers stated that the annealing dataset size was 40 billion tokens (0.02% of the total dataset size); this 40B annealing dataset was used to assess data quality. In section 3.4.3, they state that the actual annealing was done only on 40 million tokens (0.1% of the annealing data).

4.3 Llama 3.1 Post-training

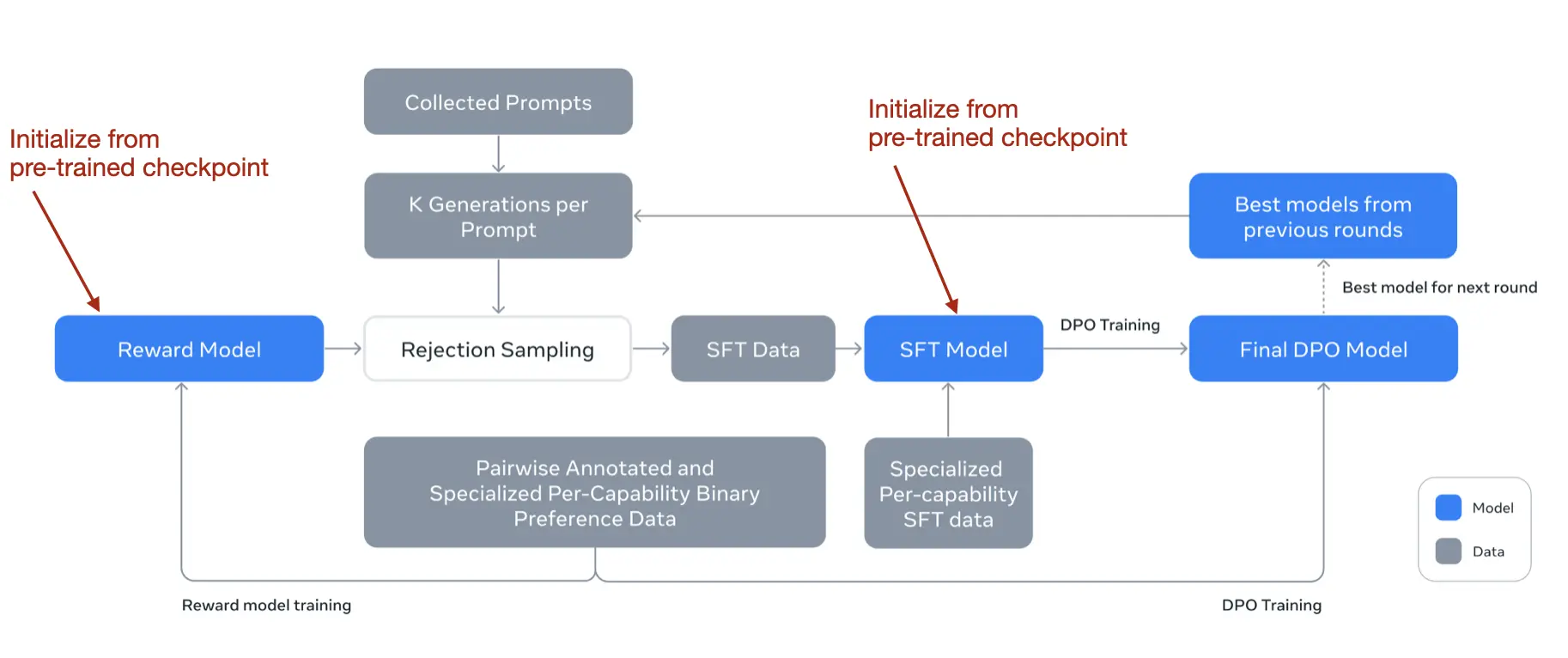

For their post-training process, the Meta AI team employed a relatively straightforward method that included supervised fine-tuning (SFT), rejection sampling, and direct preference optimization (DPO).

They observed that reinforcement learning algorithms like RLHF with PPO were less stable and more challenging to scale compared to these techniques. It’s worth noting that the SFT and DPO steps were iteratively repeated over multiple rounds, incorporating both human-generated and synthetic data.

Before describing the further details, their workflow is illustrated in the figure below.

Note that even though they used DPO, they also developed a reward model as you’d do in RLHF. Initially, they trained the reward model using a checkpoint from the pre-training phase, utilizing human-annotated data. This reward model was then used for the rejection sampling process, helping to select appropriate prompts for further training.

In each training round, they applied model averaging techniques not only to the reward model but also to the SFT and DPO models. This averaging involved merging the parameters from recent and previous models to stabilize (and improve) performance over time.

For those interested in the technical specifics of model averaging, I discussed this topic in the section “Understanding Model Merging and Weight Averaging” of my earlier article Model Merging, Mixtures of Experts, and Towards Smaller LLMs.

To sum it up, at the core, it’s a relatively standard SFT + DPO stage. However, this stage is repeated over multiple rounds. Then, they sprinkled in a reward model for rejection sampling (like Qwen 2 and AFM). They also used model averaging like Gemma; however, it’s not just for the reward models but all models involved.

4.4 Conclusion

The Llama 3 models remain fairly standard and similar to the earlier Llama 2 models but with some interesting approaches. Notably, the large 15 trillion token training set distinguishes Llama 3 from other models. Interestingly, like Apple’s AFM model, Llama 3 also implemented a 3-stage pre-training process.

In contrast to other recent large language models, Llama 3 did not employ knowledge distillation techniques, opting instead for a more straightforward model development path. For post-training, the model utilized Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) instead of the more complex reinforcement learning strategies that have been popular in other models. Overall, this choice is interesting as it indicates a focus on refining LLM performance through simpler (but proven) methods.

5. Main Takeaways

What can we learn from these four models discussed in this article: Alibaba’s Qwen 2, Apple’s foundational models (AFM), Google’s Gemma 2, and Meta’s Llama 3?

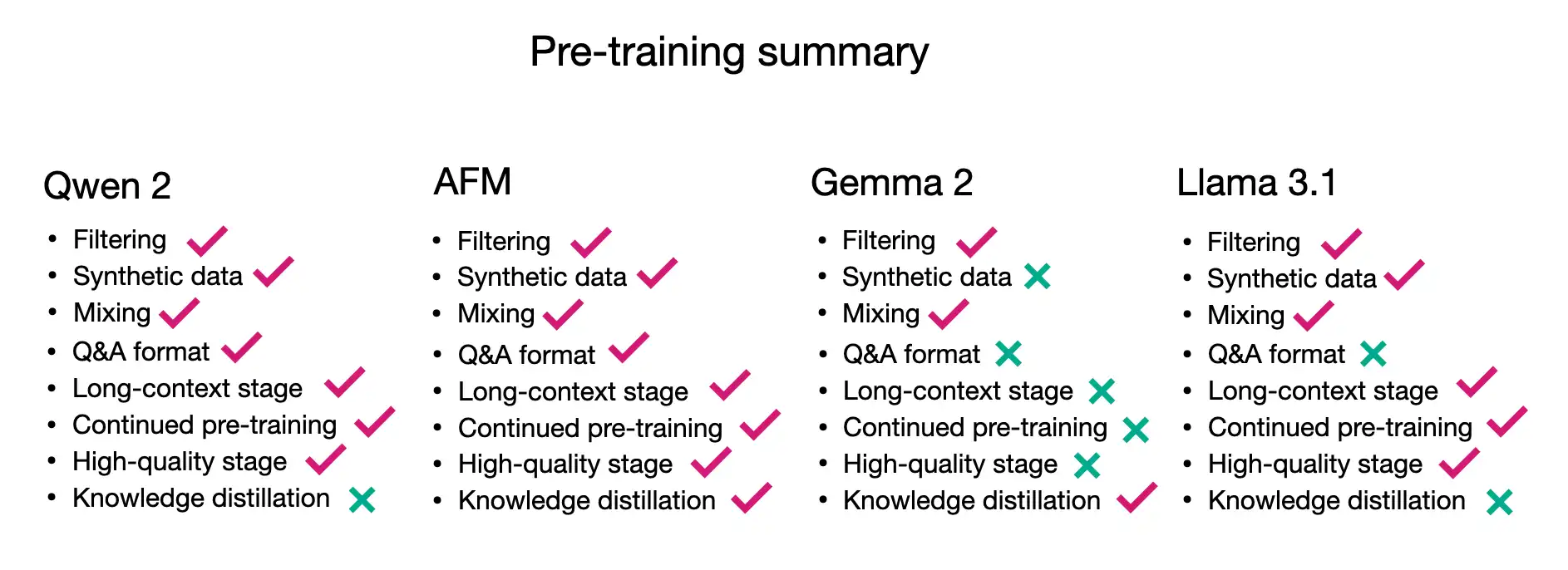

All four models take somewhat different approaches to pre-training and post-training. Of course, methodologies overlap, but no training pipeline is quite the same. For pre-training, a shared feature seems to be that all methods use a multi-stage pre-training pipeline, where a general core pre-training is followed by a context lengthening and sometimes high-quality annealing step. The figure below shows again the different methods employed in pre-training at a glance.

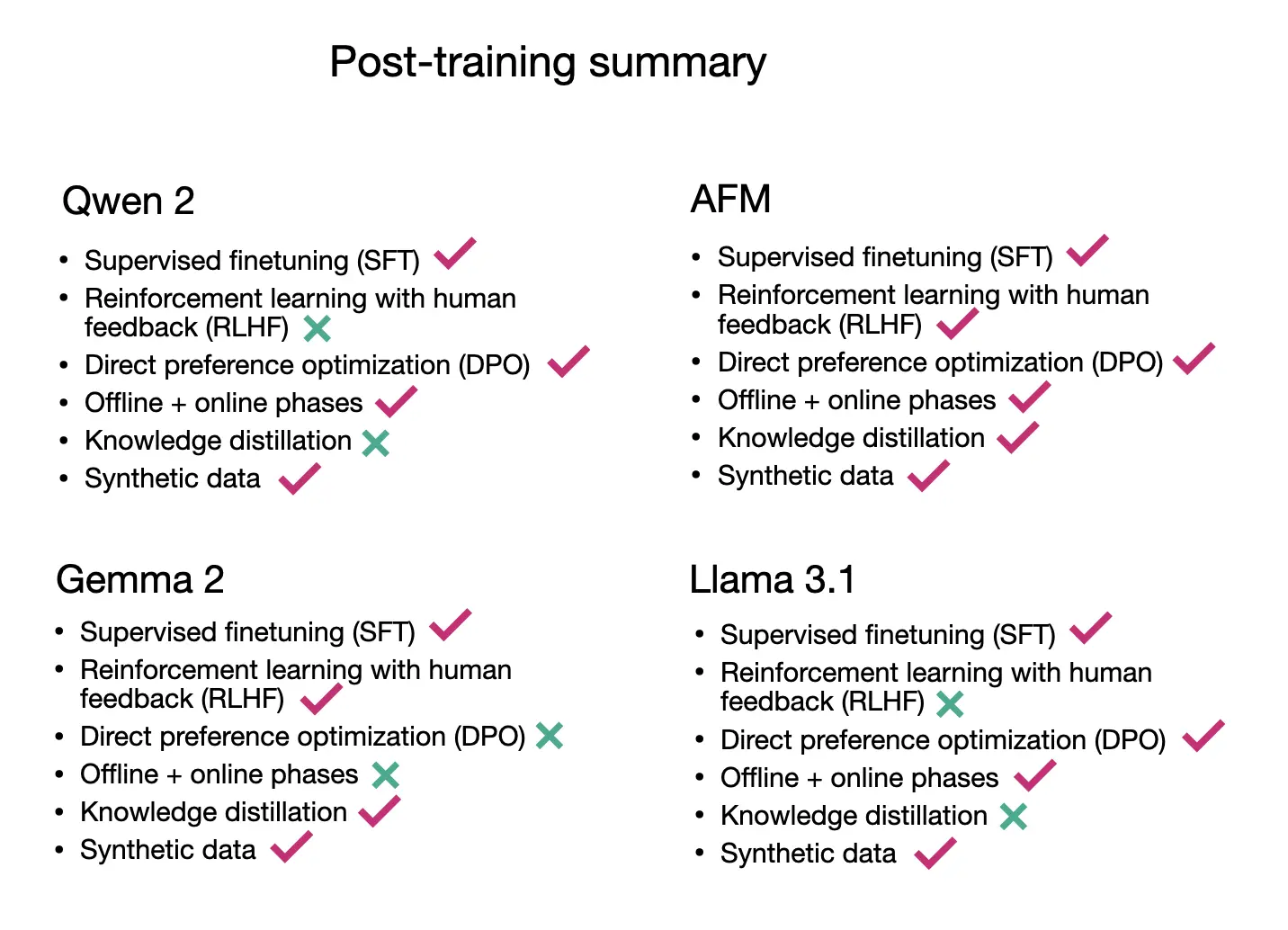

When it comes to post-training, also none of the pipelines was exactly the same. It seems that rejection sampling is now a common staple in the post-training process. However, when it comes to DPO or RLHF, there’s no consensus or preference (no pun intended) yet.

So, in all, there is no single recipe but many paths to developing highly-performant LLMs.

Lastly, the four models perform in the same ballpark. Unfortunately, several of these models have not made it into the LMSYS and AlpacaEval leaderboards, so we have no direct comparison yet, except for the scores on multiple-choice benchmarks like MMLU and others.

If you read the book and have a few minutes to spare, I'd really appreciate a brief review. It helps us authors a lot!

Your support means a great deal! Thank you!